A sacred cow is a belief, tradition, or idea held as unquestionably true or untouchable, often defended without scrutiny. It serves as a psychological or cultural anchor, resisting challenge due to its perceived importance or emotional weight. Sola scriptura—the Protestant doctrine asserting that the Bible alone is the ultimate, infallible authority for Christian faith, doctrine, and practice—functions precisely as such a sacred cow in many evangelical and Protestant circles. While presented as a humble submission to divine authority, it often operates as an epistemological fortress that insulates its premises from critique, creating what I call “deductive rigidity”—a system that becomes dogmatic and controlling when premises are insulated from all challenge. This rigidity not only stifles the abductive reasoning essential to genuine truth-seeking but contains within itself a fatal logical flaw that undermines its very foundation.

The most immediate problem with sola scriptura is its self-referential paradox. If human reason is portrayed as fundamentally corrupted or unreliable—as many proponents claim when (mis)citing passages like 1 Corinthians 2:14 (“The person without the Spirit does not accept the things that come from the Spirit of God”)—then how can corrupted reason reliably determine that Scripture is true? How can it correctly interpret Scripture’s meaning? How can it distinguish between valid and fallacious reasoning when examining Scripture? Either human minds can genuinely apprehend truth, or appeals to revelation have no rational footing. When proponents of sola scriptura claims that “only God has the keys to truth and that reason is trustworthy only when it agrees with scripture,” it creates an impossible bind: no human being could ever know that scripture is true, since any act of knowing would itself rely on the “human understanding” declared untrustworthy. The stance collapses into self-contradiction.

This problem extends beyond mere biblical interpretation to the very foundations of how we pursue truth. When premises cannot be challenged—when Scripture is treated as the only infallible authority with no possibility of new revelation—the system becomes self-protecting rather than truth-seeking. Evidence that contradicts established interpretations must be reinterpreted, dismissed, or declared “outside the scope” of relevant truth. This creates what Karl Popper would call a “non-falsifiable” system—one that cannot be proven wrong because any contradictory evidence is reinterpreted to fit the framework. In practice, this means abductive reasoning—the creative process of generating hypotheses, testing them against evidence, and revising understanding—becomes obsolete for discovering fundamental truth. The system declares all truth already contained in Scripture, transforming truth-seeking into mere confirmation-seeking.

Consider the most commonly cited proof-text for sola scriptura: 2 Timothy 3:16-17. “All Scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness.” But this passage contains the first fatal flaw in sola scriptura’s logic. When Paul wrote these words around 64-67 AD, “Scripture” (*graphē* in Greek) referred exclusively to the Old Testament writings—the “Sacred Writings” of Judaism. The New Testament as we know it didn’t exist; most of its books hadn’t even been written. Paul couldn’t possibly have been referring to a closed 66-book canon that wouldn’t be formalized for another three centuries. This single historical fact unravels sola scriptura’s central claim at its most basic level. Other passages suffer from the same anachronistic problem: Jesus quoting Deuteronomy may affirm Old Testament authority, not a future New Testament compilation; Revelation’s warning applies only to John’s own prophecy, not to an entire biblical canon.

The New Testament canon was formalized at the Council of Hippo in 393 AD and confirmed at Carthage in 397 AD. Crucially, these councils didn’t “invent” the canon; they recognized writings already in widespread use by churches across the Mediterranean world. The process of canonization was organic, emerging from centuries of communal discernment about which texts genuinely reflected apostolic teaching. No biblical author could possibly have known which writings would later form the Christian Bible—Paul didn’t know his letters would become Scripture, John didn’t know Revelation would be considered the “last book,” and none operated with the concept of a closed New Testament canon.

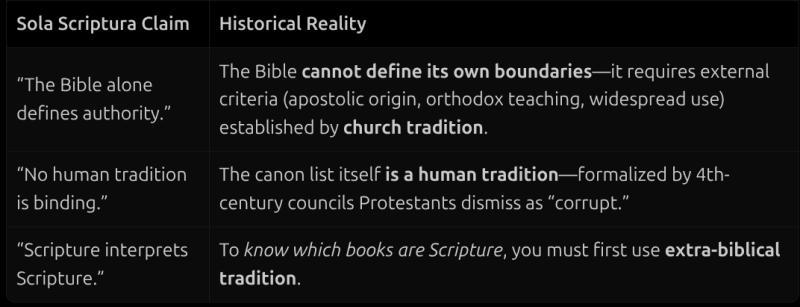

This brings us to the heart of the matter: Why This Matters: The Unavoidable Dependence on Tradition. Sola scriptura claims to reject tradition as an authority, yet it depends entirely on tradition to define what “Scripture” even is. Protestants appeal to the 397 AD Council of Carthage—a tradition-based authority—to justify their 66-book Bible while condemning Catholic tradition as “unbiblical.” Martin Luther himself rejected Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation as “less authoritative,” proving that without some tradition, canon determination becomes entirely subjective. The doctrine creates an impossible paradox where it simultaneously requires and rejects the very thing that makes it possible.

The irony is profound and inescapable. Protestants rely on early church tradition (the Muratorian Fragment, Athanasius’ Festal Letter, Hippo and Carthage councils) to identify Scripture, then turn around and condemn tradition as an authority. They accuse Catholics of “adding” to Scripture while simultaneously depending on Catholic councils to tell them what Scripture *is*. This isn’t merely inconsistent—it’s a complete epistemological collapse. As historian Jaroslav Pelikan observed, “Tradition is the living faith of the dead; traditionalism is the dead faith of the living.” Sola scriptura has devolved into traditionalism—elevating a specific historical tradition (the 4th-century canon list) while denying all tradition.

Sola scriptura is self-defeating. It requires the authority of tradition to identify Scripture—but then denies tradition’s authority. This isn’t a minor logical hiccup; it’s the doctrine’s fatal flaw. The Bible never claimed to be a self-interpreting, closed canon that could operate independently of the community that birthed it. Instead, it emerged from the lived tradition of the early church—the Gospels written decades after Jesus’ ministry, letters composed in response to specific community needs, apocalyptic literature addressing immediate concerns. The canon wasn’t dropped from heaven as a finished product; it was discerned through centuries of communal wrestling with which writings most faithfully testified to the living Christ.

This realization doesn’t undermine Scripture—it liberates it. It frees us from the impossible burden of sola scriptura’s self-contradiction, allowing Scripture to speak within the living tradition of the communities that birthed it. The Bible never claimed to be a self-contained, self-interpreting authority that could function apart from the community of believers. Rather, it points us to Christ, the living Logos (John 1:1, 14), who promised to be with his church “always, to the very end of the age” (Matthew 28:20) and to build his church on the rock of apostolic confession (Matthew 16:18). Scripture functions as it was meant to when understood within the context of the church—the “pillar and foundation of the truth” (1 Timothy 3:15)—guided by the same Spirit who inspired its writing.

The question “Where does the Bible say the Bible is the sole authority?” answers itself: It doesn’t—because it can’t. The Bible contains no verse declaring that the completed biblical canon is the sole infallible authority for Christian faith. This isn’t a weakness of Scripture; it’s a weakness of a doctrine that asks the Bible to do something it was never designed to do. Scripture was never meant to function as a self-enclosed legal code that operates independently of the community it creates. It was written to be read, interpreted, and lived out within the fellowship of believers who continue Christ’s mission in the world. By insisting otherwise, sola scriptura inadvertently creates a subtle idolatry where the Bible becomes an object of worship rather than a witness to the living God, placing the written word above the living Word it proclaims.

In the end, recovering the Bible from sola scriptura doesn’t diminish its authority—it restores its proper function. The Bible points us beyond itself to the living Christ who works through his people (Ephesians 4:11-13), not to a closed canon that functions as a substitute for the living Logos. When we release Scripture from the impossible burden of sola scriptura’s self-contradiction, we rediscover its true power: not as a weapon in doctrinal battles, nor as an idol to be worshiped in place of the God it reveals, but as a witness to the One who said, “I am the way, the truth, and the life” (John 14:6). This isn’t a retreat from biblical authority—it’s a return to the Bible’s own testimony about itself and the community it calls into being. The path forward isn’t found in rigid certainty, but in humble truth-seeking—where Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience work together under the guidance of the Spirit who leads us “into all truth” (John 16:13).

Did you enjoy the article? Show your appreciation and buy me a coffee:

Bitcoin: bc1qmevs7evjxx2f3asapytt8jv8vt0et5q0tkct32

Doge: DBLkU7R4fd9VsMKimi7X8EtMnDJPUdnWrZ

XRP: r4pwVyTu2UwpcM7ZXavt98AgFXRLre52aj

MATIC: 0xEf62e7C4Eaf72504de70f28CDf43D1b382c8263F

THE UNITY PROCESS: I’ve created an integrative methodology called the Unity Process, which combines the philosophy of Natural Law, the Trivium Method, Socratic Questioning, Jungian shadow work, and Meridian Tapping—into an easy to use system that allows people to process their emotional upsets, work through trauma, correct poor thinking, discover meaning, set healthy boundaries, refine their viewpoints, and to achieve a positive focus. You can give it a try by contacting me for a private session.