I sometimes joke, deadpan, “I’m the most humble person I’ve met—but I’m not modest.” It’s not a flex; it’s a pointer to a common confusion many people never examine. We often applaud the quiet performance of modesty while missing the sturdier virtue of humility. When truth matters more than optics, that mix-up becomes hard to ignore, because people reward the surface and punish the substance.

I sometimes joke, deadpan, “I’m the most humble person I’ve met—but I’m not modest.” It’s not a flex; it’s a pointer to a common confusion many people never examine. We often applaud the quiet performance of modesty while missing the sturdier virtue of humility. When truth matters more than optics, that mix-up becomes hard to ignore, because people reward the surface and punish the substance.

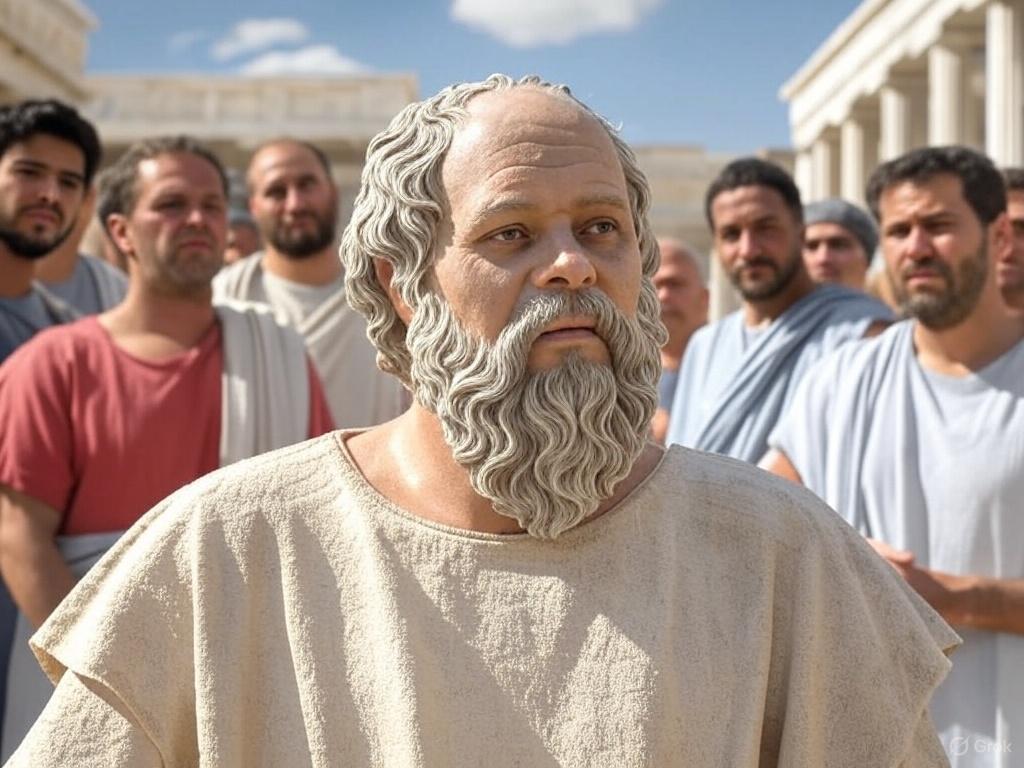

Socratic humility is the intellectual virtue of recognizing and embracing the limits of one’s knowledge, fostering openness to learning and growth. It counters arrogance by encouraging a continuous quest for truth without diminishing self-worth.

Intellectual Humility: Having a consciousness of the limits of one’s knowledge, including a sensitivity to circumstances in which one’s native egocentrism is likely to function self-deceptively; sensitivity to bias, prejudice and limitations of one’s viewpoint. Intellectual humility depends on recognizing that one should not claim more than one actually knows. It does not imply spinelessness or submissiveness. It implies the lack of intellectual pretentiousness, boastfulness, or conceit, combined with insight into the logical foundations, or lack of such foundations, of one’s beliefs. ~“The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools (Thinker’s Guide Library)” by Richard Paul & Linda Elder.

Humility, properly understood, is Socratic. It is not about downplaying yourself; it is the disciplined self-awareness of limitation. Socratic humility is the intellectual virtue of recognizing and embracing the limits of one’s knowledge, which keeps you open to learning and growth. It counters arrogance not by shrinking the self, but by keeping attention on what can be known and what must still be tested. This aligns with Richard Paul and Linda Elder’s account: be conscious of the limits of your knowledge, alert to how egocentrism, bias, and your vantage point can mislead, and refuse to claim more than you can justify.

This kind of humility is accuracy, not smallness. It grants your real strengths their due and your blind spots the light they need. It speaks plainly about what you know, what you don’t, and what you are still investigating. It does not imply spinelessness or submissiveness; it pairs courage with openness and self-respect with a standing invitation to correction.

Modesty is different. Modesty is an outward style—restraint in speech, dress, and demeanor—aimed at avoiding undue attention. It is shaped by social norms and varies by culture and context, and it can be sincere, strategic, or merely habitual. Because it’s presentation rather than conviction, it doesn’t necessarily tell you much about a person’s relationship to truth. It can align with humility, but it can also substitute for it.

We confuse the two because they often look alike from the outside. Both tend to avoid chest-beating. Both may deflect praise or speak quietly. Language blurs the line as well, since we often use “humble” to describe modest acts even when the inner posture is unknown. The real difference is intent and depth—what you’re aiming at and how you form your beliefs.

Consider a simple scene after a win. One person says, “Oh, it was nothing.” That might be modesty (politeness or image management), or it might be humility (a sober recognition that many things had to go right). Another says, “Thank you—I worked hard on this.” That could be arrogance, or it could be humility that refuses to lie about effort and skill. The issue isn’t volume; it’s accuracy and honesty.

Socrates models humility without downplaying. “I know that I know nothing” captures his stance toward knowledge: relentless about limits, open to correction, and devoted to inquiry. He did not claim special status; he forced his own ideas and everyone else’s to answer to reasons. He challenged the powerful in public and defended his life’s work without groveling—bold in presentation, humble in method.

You can see the same pattern now. Picture a scientist who openly admits that most of the universe remains a mystery, while speaking with unapologetic confidence about their specific domain and enjoying hard debate. That isn’t modest, but it can be genuinely humble: no claims beyond evidence, no belief in inherent superiority, and an open door to being shown wrong. The voice may be loud, the wardrobe flashy, but the standard is still truth over egocentrism.

Because modesty imitates humility’s outer signs, it can produce a convincing counterfeit. A person can whisper, dress down, and decline credit while privately nursing contempt or maneuvering for advantage. The performance earns a halo because we reward the look of restraint even when its purpose is impression management. We are prone to misread soft tones as depth and directness as conceit, which flips incentives in unhealthy ways.

Overreliance on modesty can also interfere with real humility. Arrogance can hide inside restraint: “Look how unlike those show-offs I am.” Fear of perception can replace attention to facts: “Will they think I’m arrogant if I speak plainly?” Chronic self-suppression can blunt self-knowledge: “I’ll pretend I don’t know this,” until you lose touch with what you do know. All of this feeds egocentrism by making the audience, not reality, the main judge.

Socratic humility cuts through these traps by training attention on evidence, logic, and the live possibility of error. It notices the pull of egocentrism, bias, and narrow perspective, and treats them as hazards to be managed rather than identities to defend. It builds the reflex to ask, “What do I know? How do I know it? Where could I be wrong?” That mindset keeps you curious and correctable without diminishing your worth.

In practice, this looks like habits you can train. Define your terms before arguing so you don’t fight over shadows. Ask for the evidence behind a claim and separate what’s certain from what’s probable. Say “I don’t know yet” when that’s the truth, and update your view when better reasons appear. None of this requires you to shrink; it requires you to be precise.

Humility also changes how you own your strengths. You can say, “Yes, I’m skilled at this,” without implying you’re above others, because skill is earned, specific, and bounded. You can add, “Here are the limits of that skill,” without pretending they don’t matter. Accept earned praise with a simple “Thank you,” and accept fair critique with “Good point—I’ll adjust.” That’s humility; downplaying to look small is just another form of self-absorbed performance.

In conflict, humility is a mirror. When facing bluster or overconfidence, you don’t need a sledgehammer. You ask clarifying questions, follow implications, and let unsupported claims collapse under their own weight. If there’s substance, it will stand; if there isn’t, the gap between confidence and reality shows itself.

Here’s the plain-language point about presentation: acting modest often works like camouflage. People lower their guard, ask fewer hard questions, and give the benefit of the doubt to the person who seems unassuming. By contrast, plain, direct, truth-first speech tends to draw more scrutiny and pushback, even when it is accurate. Modesty can be weaponized in these moments. A skilled operator adopts a self-effacing style to lower defenses and gain trust, all while steering credit or decisions. They murmur, “I’m just here to help,” and later, “Nobody wanted this outcome,” after they’ve quietly secured it.

To protect yourself from weaponized modesty, insist on specifics and accountability. Ask, “What exactly are we deciding?” “Who is responsible for what, by when, and how will we measure it?” Tie claims to evidence and terms to reciprocity so no one hides behind a soft tone. If someone uses a modest pose to dodge clarity or responsibility, set boundaries and be willing to walk away. That is not aggression; it is rational self-respect.

The line “I’m the most humble person I’ve met” can be coherent when it means, “Compared to the people I’ve encountered, I am unusually strict about claiming only what I can support, quick to correct myself, and attentive to my limits.” That’s a report about method, not a boast about rank. Tone still matters, but precision matters more, because humility is about standards for belief, not costumes for approval. You can know you practice humility well without pretending not to.

Culturally, we would benefit from rewarding accuracy over ritual self-effacement. Praise clear contributions without demanding a performance of smallness. Treat directness as a sign of responsibility rather than egocentrism, and treat coyness as a cue for more questions, not automatic virtue. This shifts status away from appearances and back toward substance.

None of this dismisses modesty in its proper place. There are contexts where restraint is courteous and wise, and where a quieter style helps others engage. But when modesty conflicts with truth, choose truth—and choose the manner that best serves it. Sometimes that’s quiet; sometimes it’s loud. Humility decides by reality, not fashion.

Socratic humility keeps the light on what is, not on how you look. It lets you be confident where you have earned it and cautious where you have not. It anchors courage with openness and pairs self-respect with a constant readiness to revise. It is fuel for growth, not a costume for approval. You do not need to dim yourself to be humble. You need to be honest about where you shine and where you don’t, committed to learning, and unwilling to pretend. That is humility without downplaying—Socratic in spirit, exacting in practice, and fully compatible with a life lived in truth. It is a virtue that strengthens both clarity and character because it serves reality first.

Did you enjoy the article? Show your appreciation and buy me a coffee:

Bitcoin: bc1qmevs7evjxx2f3asapytt8jv8vt0et5q0tkct32

Doge: DBLkU7R4fd9VsMKimi7X8EtMnDJPUdnWrZ

XRP: r4pwVyTu2UwpcM7ZXavt98AgFXRLre52aj

MATIC: 0xEf62e7C4Eaf72504de70f28CDf43D1b382c8263F

THE UNITY PROCESS: I’ve created an integrative methodology called the Unity Process, which combines the philosophy of Natural Law, the Trivium Method, Socratic Questioning, Jungian shadow work, and Meridian Tapping—into an easy to use system that allows people to process their emotional upsets, work through trauma, correct poor thinking, discover meaning, set healthy boundaries, refine their viewpoints, and to achieve a positive focus. You can give it a try by contacting me for a private session.