What is the moral code of altruism? The basic principle of altruism is that man has no right to exist for his own sake, that service to others is the only justification of his existence, and that self-sacrifice is his highest moral duty, virtue and value.

Do not confuse altruism with kindness, good will or respect for the rights of others. These are not primaries, but consequences, which, in fact, altruism makes impossible. The irreducible primary of altruism, the basic absolute, is self-sacrifice—which means; self-immolation, self-abnegation, self-denial, self-destruction—which means: the self as a standard of evil, the selfless as a standard of the good.

Do not hide behind such superficialities as whether you should or should not give a dime to a beggar. That is not the issue. The issue is whether you do or do not have the right to exist without giving him that dime. The issue is whether you must keep buying your life, dime by dime, from any beggar who might choose to approach you. The issue is whether the need of others is the first mortgage on your life and the moral purpose of your existence. The issue is whether man is to be regarded as a sacrificial animal. Any man of self-esteem will answer: “No.” Altruism says: “Yes.”

~Ayn Rand

I reject altruism, public service, and the public good as the moral justification of free enterprise. Altruism is what is destroying capitalism. Adam Smith was a brilliant economist, I agree with many of his economic theories, but I disagree with his attempt to justify capitalism on altruistic grounds. My defense of capitalism is based on individual rights, as was the American founding fathers, who were not altruists. They did not say “man should exist for others”, they said “he should pursue his own happiness.” ~Ayn Rand

The essence of altruism is self-sacrifice, if you do something for another that involves harm to yourself, that is altruism, but voluntarily giving something to another who hasn’t earned it, that’s morally neutral, you may or may not have a good reason for doing it. As a principle, nobody would think of forbidding all voluntary giving; judging what giving is proper depends on the context of the situation, on the relationship of the two persons involved. ~Ayn Rand

The basic principle of altruism is that man has no right to exist for his own sake, that service to others is the only justification of his existence, and that self-sacrifice is his highest moral duty, virtue and value. ~Ayn Rand, “The Virtue of Selfishness“

The “bad human” program is an internalized and often subconscious belief system that convinces individuals they are inherently flawed, guilty, or unworthy at their core. This core belief places individuals in a state of perpetual moral debt, compelling them to constantly seek external validation or “atone” for their existence through mechanisms like self-sacrifice.

Many of us are driven by a powerful impulse to help, to fix, and to save others. On the surface, this drive is celebrated as the pinnacle of moral virtue. We are taught that to live for others is the noblest calling. But what if this compulsion to rescue is not born from a place of strength and overflowing benevolence, but from a deep, often unconscious wound? What if the celebrated ideal of altruism is, in fact, a coping mechanism for a pervasive, culturally ingrained belief that we are, at our core, fundamentally flawed—a program running in the background of the human psyche that tells us we are a “bad human”?

To understand this connection, we must first define our terms with precision. Altruism is not the same as kindness, generosity, or goodwill. These are positive actions that can arise from a genuine sense of abundance and respect for others. Altruism, as a moral philosophy, demands something far more specific and insidious. As Ayn Rand defined it, “The basic principle of altruism is that man has no right to exist for his own sake, that service to others is the only justification of his existence, and that self-sacrifice is his highest moral duty, virtue and value.” It is the doctrine of self-immolation, where the self is treated not as something to be developed, but as something to be given away.

This is where the “bad human” program enters the picture. This is the internalized belief that we are inherently guilty, selfish, or unworthy. It’s a feeling of carrying a deep, unpayable debt for the crime of simply existing. For a person convinced of their own inadequacy, the doctrine of altruism offers a tempting, if ultimately fraudulent, path to redemption. If you believe you are fundamentally bad, you cannot find worth within yourself. Therefore, you must seek it externally by negating the very thing you find so shameful: your self. By sacrificing for others, you attempt to prove, both to the world and to yourself, that you are not the “bad human” you secretly fear you are.

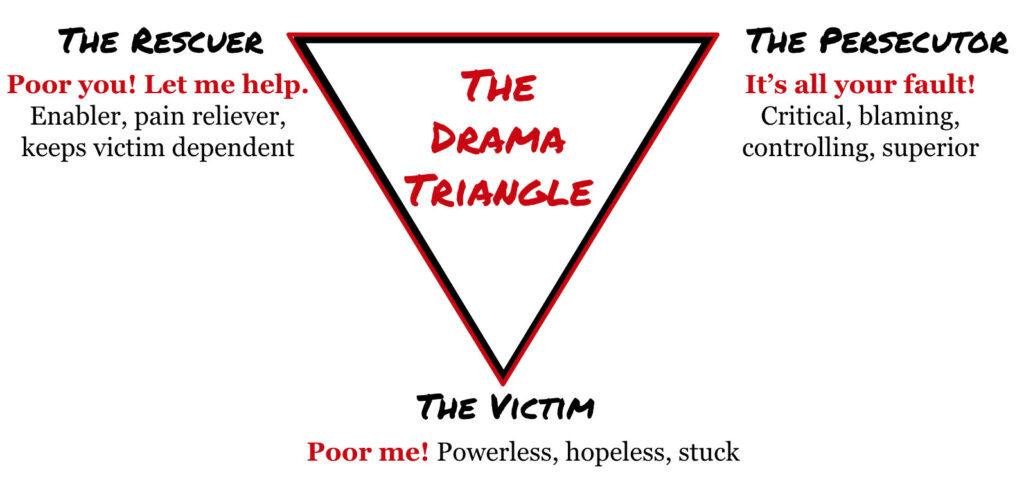

Karpman’s Drama Triangle is a psychological model describing dysfunctional social interactions through three roles: the victim, who feels powerless and seeks rescue; the persecutor, who blames or oppresses; and the rescuer, who intervenes to “save” but often perpetuates the cycle. These roles create a dynamic of blame, dependency, and conflict, trapping participants in unhealthy patterns.

This dynamic places one squarely in the role of the “Rescuer” within the psychological framework known as the Karpman Drama Triangle. The triangle describes a dysfunctional pattern of interaction involving three roles: the Victim, the Persecutor, and the Rescuer. While seemingly distinct, all three roles are born from a disempowered state. The Rescuer, fueled by the need to atone for their perceived badness, seeks out Victims to save. This act of service isn’t about genuine empowerment; it’s about validating the Rescuer’s own moral worth and giving them a temporary reprieve from their inner guilt. They need a Victim to feel like a hero.

The trap of the Drama Triangle is that all three roles are codependent and perpetuate a cycle of powerlessness. At the heart of each role is the Victim mindset—the core belief of the “bad human” program. The Persecutor acts out this feeling of worthlessness by projecting it onto others, embracing the power that comes from causing harm. The Victim embodies the powerlessness directly. And the Rescuer tries to bypass their own inner Victim by focusing on the victimhood of others, gaining a sense of moral superiority without ever having to do the difficult inner work of resolving their own feelings of inadequacy. Altruism provides the perfect moral cover for this behavior, dignifying the Rescuer’s neediness as virtue.

The Victim, in turn, weaponizes their perceived powerlessness, demanding that others sacrifice themselves to prove that the Victim is good enough and worthy enough of love. This demand stems directly from their own conviction that they are a “bad human,” creating a relentless psychological test for those around them with the mentality: “prove to me again and again that I am a good human, because I don’t believe it.” If and/or when these demands for reassurance inevitably go unmet, the Victim can quickly become the villain, shifting into the Persecutor role to punish those who failed to prop up their fragile self-worth. This fluid instability is a hallmark of the triangle, as the Rescuer can also turn into a villain if they do not receive the feedback and appreciation that they feel their sacrifice deserves.

Transactional Love is a conditional exchange where affection or care is offered with the expectation of receiving something in return, such as validation or reciprocation. It operates like a contract, driven by external motives and often tied to a sense of obligation or debt.

When self-sacrifice is held as the highest good, your life is no longer your own. You are taught that the needs of others constitute a moral claim on your time, your energy, your resources, and your very existence. This turns morality into a transaction where your life is perpetually mortgaged to the demands of others. As Rand powerfully articulated, “The issue is whether you must keep buying your life, dime by dime, from any beggar who might choose to approach you.” The endpoint of this logic is the view of the human being as a sacrificial animal, whose purpose is to be consumed by the collective. A person with genuine self-esteem—an earned confidence in their own moral worth and competence—rejects this premise entirely.

The alternative to this cycle of atonement is not callous indifference, but the profound and demanding work of building an authentic Self. This is the path of individualism, grounded not in whims, but in reason and principle. It involves cultivating inner virtues like Socratic humility—the honest recognition of what you do and do not know—and the intellectual courage to face uncomfortable truths about yourself and the world. Through this dedicated self-work, one moves from the feeling of being a “bad human” to achieving a state of earned innocence, where one’s goodness is not a performance for others but a foundational premise of one’s own character.

He [Jesus] sat down opposite the treasury and observed how the crowd put money into the treasury. Many rich people put in large sums. A poor widow also came and put in two small coins worth a few cents. Calling his disciples to himself, he said to them, “Amen, I say to you, this poor widow put in more than all the other contributors to the treasury. For they have all contributed from their surplus wealth, but she, from her poverty, has contributed all she had, her whole livelihood.” ~Mark 12:41-44 (NABRE)

Many historical and religious narratives have been misinterpreted to support the altruistic ideal. Consider the leaders of Jesus’ day, criticized for their performative goodness—making grand offerings so all could see how righteous they were. This is transactional morality, an attempt to purchase status from God and society. While some try to counter this by quietly sacrificing their lives in service, they often miss the deeper point. The story of the widow’s two mites, for example, is not about the virtue of giving away your last dollar to an institution. It’s a metaphor for a much greater sacrifice.

The widow’s offering represents the sacrifice of one’s attachment to external validation and status—the very things she, in her poverty, had nothing left of. Her gift was total because she was giving her whole self to a higher principle, not for the sake of others, but for the sake of her own soul’s integrity. The true spiritual work is not to sacrifice for others, but to sacrifice the parts of yourself that are false: your victimhood, your need for control, your unearned moral superiority, and the entire persona built to hide the “bad human” you fear you are. This is the great work of self-creation.

This principle is ancient, echoed in the story of Cain and Abel. Abel’s sacrifice was accepted because it was a genuine offering, symbolic of successful inner work and the cultivation of a true Self. Cain’s was rejected because it was the offering of a divided and resentful heart, leading not to introspection, but to envy and murder. He hated his brother not for his possessions, but for his state of being—for the earned innocence Cain himself had failed to achieve. The sacrifice God, or Truth, truly desires is the forfeiture of your own illusions.

Non-Transactional Love is given freely without expecting repayment, rooted in genuine care and intrinsic motivation. It prioritizes authentic connection and truth, unbound by calculations or external rewards.

When we ground our interactions in this new understanding, we can move from a transactional mindset to one of non-transactional connection. The Rescuer operates on a foundation of *transactional love*: “I will give you this piece of myself, and in return, I receive the feeling of being a good person.” It is an exchange rooted in need. Non-transactional love, however, is given freely from a place of wholeness, without expecting repayment. It is rooted in a genuine appreciation for another’s existence and a desire to connect with them based on shared values and mutual respect.

Agape love, in traditional Greek usage, refers to a form of love that prioritizes the well-being of others without expecting anything in return, often associated with divine or universal compassion, and is distinctly non-transactional as it seeks no reciprocation or zoomed in personal benefit, deferring instead to a zoomed out “bigger picture” personal benefit. In the New Testament, agape is elevated as the highest form of love, exemplified by God’s empathetic love for humanity and Jesus’ teachings and crucifixion, such as loving one’s enemies and neighbors as oneself, transcending the transactional debt accrued by sin.

This brings us to the concept of agape. Often misinterpreted as selfless, sacrificial love for others, agape can be understood as a non-transactional love for a higher principle or a “bigger picture.” It is not about negating the self for another person, but about aligning the self with what is true, good, and beautiful. In this light, agape is the love for one’s own highest potential and the dedication required to achieve it. It is a love for reason, for justice, and for the flourishing of human life, starting with one’s own.

This kind of love naturally results in benevolence toward others, but it does so as a consequence of self-respect, not as a substitute for it. A person who has done the work to build their own character interacts with others from a position of strength and integrity. Their kindness is not a payment on a moral debt, but an expression of their own well-realized humanity. They can help others without needing to rescue them, offering support that empowers rather than creates dependency.

Ultimately, the path to becoming a truly good person does not lie in denying the self, but in building a self worthy of esteem. It is a path of dedicated inner work, of cultivating virtues like Socratic humility, empathy, reason, integrity, and earned innocence. From the foundation of a whole and integrated character, acts of kindness and generosity aren’t viewed as sacrifices. Instead, they become expressions of an overflowing spirit, offered freely and joyfully from one sovereign individual to another. This is the virtue of a rational being, not the duty of a sacrificial animal, and it is a gift not only to yourself, but to anyone whose life you touch.

Did you enjoy the article? Show your appreciation and buy me a coffee:

Bitcoin: bc1qmevs7evjxx2f3asapytt8jv8vt0et5q0tkct32

Doge: DBLkU7R4fd9VsMKimi7X8EtMnDJPUdnWrZ

XRP: r4pwVyTu2UwpcM7ZXavt98AgFXRLre52aj

MATIC: 0xEf62e7C4Eaf72504de70f28CDf43D1b382c8263F

THE UNITY PROCESS: I’ve created an integrative methodology called the Unity Process, which combines the philosophy of Natural Law, the Trivium Method, Socratic Questioning, Jungian shadow work, and Meridian Tapping—into an easy to use system that allows people to process their emotional upsets, work through trauma, correct poor thinking, discover meaning, set healthy boundaries, refine their viewpoints, and to achieve a positive focus. You can give it a try by contacting me for a private session.