In a synchronized and deliberate march, nations across the globe are rolling out digital identification systems. From the UK and Switzerland to China and beyond, governments, in concert with globalist institutions like the World Economic Forum, are heralding these programs as the gateway to a future of streamlined efficiency and seamless access to services. Yet, beneath the veneer of technocratic progress lies a fundamental, almost revolutionary, shift in the very nature of governance. This movement is a civilizational challenge, a conscious departure from the principles of limited government and inherent rights toward a system of totalizing state control that threatens the bedrock of Western liberty.

This transformation is best understood as a conflict between two opposing legal philosophies that have vied for dominance for centuries: negative law, which protects the individual by restraining the state, and positive law, which empowers the state to create new obligations and systems. The global push for digital IDs represents the triumph of positive law, an architectural choice that is not accidental but is purposefully designed to remake the relationship between the citizen and the state, aligning it with a globalist vision antithetical to national sovereignty and individual freedom.

Positive law refers to human-made rules formally established by a governing authority. It is law that is posited, or laid down, through deliberate enactment, existing because a state has willed it so. A digital ID is a quintessential product of positive law; it has no basis in nature, tradition, or divine command. It is an entirely artificial construct, a bureaucratic imposition that does not merely regulate existing behavior but creates a new reality in which citizens must participate. It imposes new duties—the obligation to enroll, maintain, and present a state-mandated digital token simply to navigate modern life.

By contrast, negative law is rooted in restraint and prohibition. It does not create new systems but rather establishes a protective perimeter around the individual by forbidding certain governmental actions. Negative law is the language of limitation, a bulwark against tyranny that defines what a government cannot do. It forbids arbitrary seizure, protects free speech, and guarantees due process. This profound legal tradition operates from the premise that liberty is the natural, pre-political state of humanity and that the primary purpose of just law is to erect an unbreachable barrier against encroachments upon that liberty.

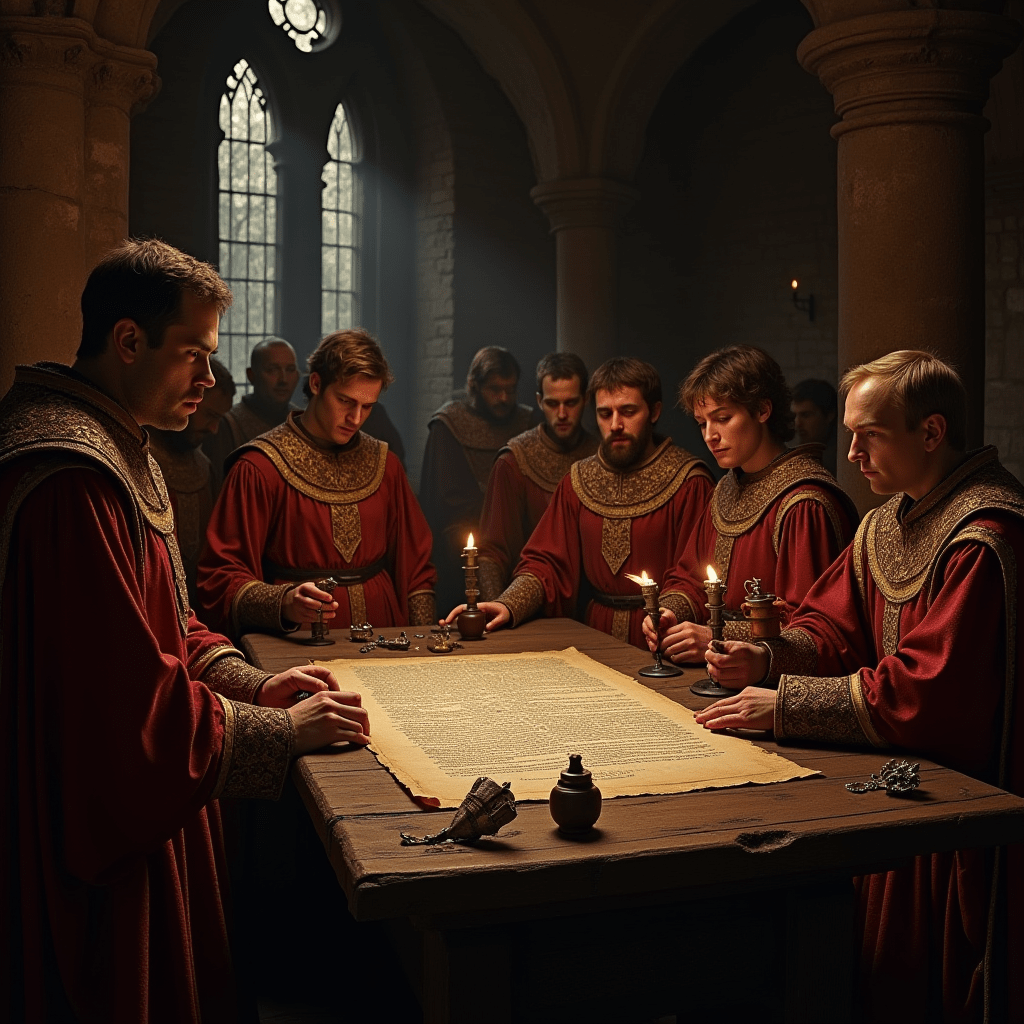

The Anglo-American legal tradition is a magnificent monument to this negative-law heritage, with its origins traceable to a muddy field at Runnymede in 1215. There, the Magna Carta was sealed, not as a grant of new privileges from the crown but as a forceful limitation imposed by the barons upon King John. Its most enduring clauses are prohibitions, setting boundaries on royal authority and establishing the revolutionary principle that even the monarch is subject to the law of the land. It was a confrontation between raw power and restraining principle that set the West on its unique path.

It is true that the Magna Carta was an imperfect document, a bargain among the elite that explicitly protected only “free men” and not the vast majority of the serf population who were bound to the land. It was far from a universal declaration of human rights. However, its genius lay not in its immediate application but in the legal and moral precedent it established: the formal, written restraint of sovereign power. This seed of negative law would eventually grow into a towering tree of liberty, providing the conceptual framework for future generations to expand upon and apply more broadly.