I have observed that Donald Trump is taking a lot of mostly non-aggressive, aka defensive, measures around the world in relationship to America and her interests, and that is what is tweaking everyone’s anger at him. This happened to us personally in the micro while living in the Europe; it was our protective actions around our family that got us into trouble, actions that would have been unnecessary had the other parties not been aggressive and presenting us with unrealistic demands, and siphoning away our agency through attempting to force arbitrary compliance. A case could be made that Trump is actually taking care of his moral obligations to his own people.

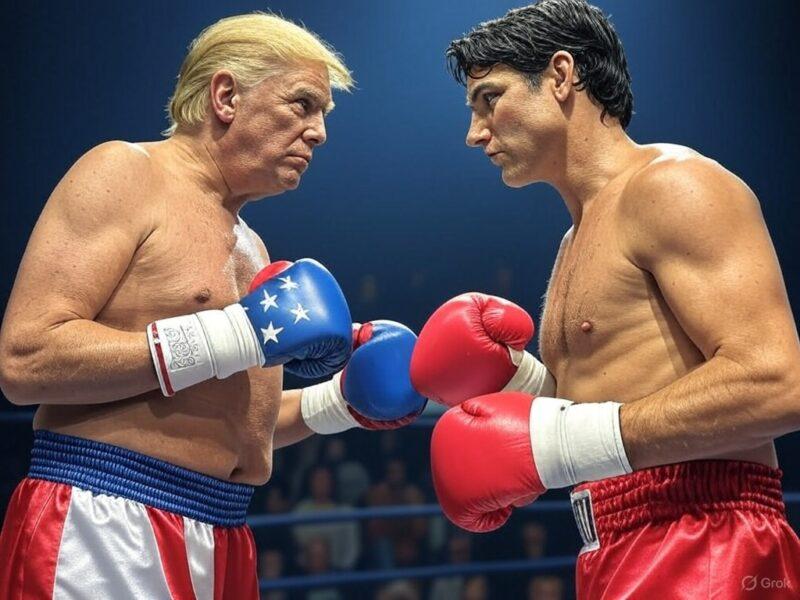

What’s going on in the Tariff wars is just more sociocentric (us vs them) media narratives at the moment, and not looking under the surface at things. Most people don’t tend to integrate or practice the character traits of humility (I don’t know it all), empathy (because I don’t know it all, I need to add perspectives), and courage (I need the courage to explore the other perspectives that might shift my worldviews). Life is complex and not simple, but the mainstream news makes life a giant, simple, and black and white game between cartoonish good guys and bad guys.

Sociocentrism is the tendency to view the world through the prism of one’s own social group, culture, or society, often assuming its norms, values, and perspectives are superior or universally valid. It’s a collective version of egocentrism—whereas the latter says “I’m the center of the universe,” sociocentrism declares “we are.” This mindset prioritizes the ingroup’s beliefs, frequently dismissing or misunderstanding those outside its boundaries. It’s a lens that shapes how people interpret reality, and it has a knack for simplifying messy social dynamics into stark, binary terms.

One of sociocentrism’s most striking effects is how it lends itself to black-and-white framing.

Black-and-white thinking is the tendency to view situations, people, or ideas in absolute, binary terms—such as good or evil, right or wrong—without recognizing nuance or complexity. It simplifies reality into rigid categories, often ignoring shades of gray that might challenge a clear-cut judgment.

When a group sees its way as the “right” way, anything that deviates gets cast as “wrong.” This isn’t just a preference—it’s a mental shortcut that reduces complexity into us vs. them, good vs. evil, truth vs. lies. For instance, a sociocentric society might paint its history as a noble saga of triumph, glossing over its own flaws or the legitimacy of opposing perspectives. It’s a unifying tactic: a clear, uncomplicated narrative rallies the group, but it also distorts reality into a cartoonish either/or.

This binary framing doesn’t just stop at storytelling—it sets the stage for deeper division, which is where balkanization enters the picture. Balkanization is the splintering of a larger society into smaller, isolated, and often antagonistic subgroups, each clinging to its own identity and worldview. Sociocentrism acts as the spark: a group doubles down on its superiority, rejecting the broader society as alien or corrupt. As that “us vs. them” mindset festers, the social fabric starts to tear, and what was once a united whole fractures into enclaves, each with its own sociocentric bubble.

The connection between sociocentrism and balkanization is a feedback loop. Sociocentrism drives the initial rift by convincing a group that its way is the only way, making coexistence with others feel like a betrayal. As the group pulls away, balkanization takes hold—think of cliques forming in a cafeteria, except these cliques have their own flags and grudges. Historical examples like the breakup of Yugoslavia show this in action: ethnic groups retreated into their own sociocentric narratives, framing each other as threats, until the nation shattered into warring pieces.

Once balkanization sets in, it supercharges sociocentrism within each faction. With less interaction across groups, there’s no need to wrestle with nuance or compromise—every splinter becomes its own echo chamber, convinced it’s the righteous core of reality. You see this today in polarized politics or online communities: as factions drift apart, their sociocentrism hardens, turning “the other” into a caricature to demonize. The less they talk, the more they shout, and the cycle deepens.

What makes this duo so potent is how self-sustaining they are. Sociocentrism justifies the split by framing outsiders as unworthy; balkanization entrenches it by cutting off dialogue. Round and round it goes, until you’re left with a fractured mess of mini-societies, each too wrapped up in its own story to see the bigger picture. It’s not just division—it’s division with conviction, where every side believes it’s the sole keeper of truth.

In the end, sociocentrism and balkanization together don’t just break societies apart—they lock them into a state of perpetual standoff. The black-and-white framing born from sociocentrism fuels the tribalism that balkanization thrives on, leaving little room for reconciliation. Whether it’s nations, ideologies, or social media bubbles, the result is the same: a world of walls, built from the inside out, where the only thing shared is distrust.

Individuation is the process by which an individual or entity, such as a person or a nation, develops a distinct and autonomous identity separate from external influences or collective dependencies. In psychology, it’s often associated with Carl Jung’s concept of becoming one’s true self by integrating various aspects of the psyche, while in a societal context, it can refer to a country asserting its unique cultural, political, or economic identity apart from historical ties or foreign pressures.

A country profoundly and rapidly isolating itself to experience a healthy “individuation” from its codependent relationships with other nations might be externally perceived as sociocentric, as outsiders could interpret its withdrawal as an arrogant assertion of national superiority or an insular rejection of global cooperation. This perception would stem from the country’s focus on forging a distinct identity—perhaps shedding historical dependencies rooted in colonial ties, economic exploitation, or unequal alliances—leading to a narrative that prioritizes its own culture, values, or sovereignty above all else. To external observers, this could look like black-and-white thinking, where the nation frames its past interdependence as inherently negative and its isolation as a moral triumph, potentially alienating allies and fueling suspicions of nationalism or xenophobia, much like how historical isolationist policies in Japan during the Edo period or North Korea’s current stance are often seen as sociocentric.

Similarly, this isolation could be mistaken for balkanization of the global community, or play along with it, if the international community fears it might fracture the global identity, the country internally, or disrupt regional stability, especially if the nation’s codependent history involved diverse regions or populations tied to neighboring states—such as Catalonia within Spain or Scotland within the UK. Outsiders might worry that the country’s push for individuation could spark separatist movements or economic disarray, as seen in Brexit’s ripple effects, where the UK’s move toward sovereignty raised concerns about the unity of the British Isles and Europe. This external perception might paint the country as retreating into a fragmented, self-absorbed state, risking conflict or division, even if the intent is to break free from unhealthy dependencies and foster a more self-reliant, unified national identity.

In reality, however, this individuation could be healthy for the nation and its people, allowing it to address long-standing imbalances, rebuild cultural confidence, and prioritize domestic well-being over external pressures. If the country’s codependent relationships historically drained resources, suppressed local industries, or eroded national identity—such as post-colonial nations struggling under neocolonial economic ties—isolating to redefine itself could foster economic diversification, cultural revitalization, and political stability. For example, a nation might use this period to invest in sustainable agriculture, strengthen local governance, or heal social divisions exacerbated by foreign influence, ultimately emerging as a more self-sufficient and equitable society. While the world might initially see sociocentrism or balkanization, the country’s internal transformation could prove a necessary and positive step toward long-term health, provided it avoids extreme nationalism and maintains some channels for dialogue.

Did you enjoy the article? Show your appreciation and buy me a coffee:

Bitcoin: bc1qmevs7evjxx2f3asapytt8jv8vt0et5q0tkct32

Doge: DBLkU7R4fd9VsMKimi7X8EtMnDJPUdnWrZ

XRP: r4pwVyTu2UwpcM7ZXavt98AgFXRLre52aj

MATIC: 0xEf62e7C4Eaf72504de70f28CDf43D1b382c8263F

THE UNITY PROCESS: I’ve created an integrative methodology called the Unity Process, which combines the philosophy of Natural Law, the Trivium Method, Socratic Questioning, Jungian shadow work, and Meridian Tapping—into an easy to use system that allows people to process their emotional upsets, work through trauma, correct poor thinking, discover meaning, set healthy boundaries, refine their viewpoints, and to achieve a positive focus. You can give it a try by contacting me for a private session.