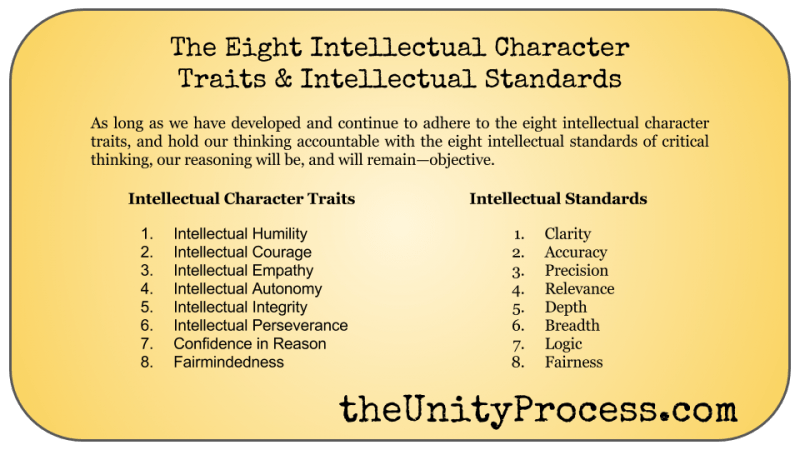

The Eight Intellectual Character Traits:

intellectual humility, intellectual courage, intellectual empathy, autonomy, integrity, intellectual perseverance, confidence in reason, and fairmindedness.

NOTE: All text below is from the book “The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools (Thinker’s Guide Library)” by Richard Paul & Linda Elder.

Intellectual Humility: Having a consciousness of the limits of one’s knowledge, including a sensitivity to circumstances in which one’s native egocentrism is likely to function self-deceptively; sensitivity to bias, prejudice and limitations of one’s viewpoint. Intellectual humility depends on recognizing that one should not claim more than one actually knows. It does not imply spinelessness or submissiveness. It implies the lack of intellectual pretentiousness, boastfulness, or conceit, combined with insight into the logical foundations, or lack of such foundations, of one’s beliefs.

Intellectual Courage: Having a consciousness of the need to face and fairly address ideas, beliefs or viewpoints toward which we have strong negative emotions and to which we have not given a serious hearing. This courage is connected with the recognition that ideas considered dangerous or absurd are sometimes rationally justified (in whole or in part) and that conclusions and beliefs inculcated in us are sometimes false or misleading. To determine for ourselves which is which, we must not passively and uncritically “accept” what we have “learned.” Intellectual courage comes into play here, because inevitably we will come to see some truth in some ideas considered dangerous and absurd, and distortion or falsity in some ideas strongly held in our social group. We need courage to be true to our own thinking in such circumstances. The penalties for non-conformity can be severe.

Intellectual Empathy: Having a consciousness of the need to imaginatively put oneself in the place of others in order to genuinely understand them, which requires the consciousness of our egocentric tendency to identify truth with our immediate perceptions of long-standing thought or belief. This trait correlates with the ability to reconstruct accurately the viewpoints and reasoning of others and to reason from premises, assumptions, and ideas other than our own. This trait also correlates with the willingness to remember occasions when we were wrong in the past despite an intense conviction that we were right, and with the ability to imagine our being similarly deceived in a case-at-hand.

Intellectual Autonomy: Having rational control of one’s beliefs, values, and inferences, The ideal of critical thinking is to learn to think for oneself, to gain command over one’s thought processes. It entails a commitment to analyzing and evaluating beliefs on the basis of reason and evidence, to question when it is rational to question, to believe when it is rational to believe, and to conform when it is rational to conform.

Intellectual Integrity: Recognition of the need to be true to one’s own thinking; to be consistent in the intellectual standards one applies; to hold one’s self to the same rigorous standards of evidence and proof to which one holds one’s antagonists; to practice what one advocates for others; and to honestly admit discrepancies and inconsistencies in one’s own thought and action.

Intellectual Perseverance: Having a consciousness of the need to use intellectual insights and truths in spite of difficulties, obstacles, and frustrations; firm adherence to rational principles despite the irrational opposition of others; a sense of the need to struggle with confusion and unsettled questions over an extended period of time to achieve deeper understanding or insight.

Confidence In Reason: Confidence that, in the long run, one’s own higher interests and those of humankind at large will be best served by giving the freest play to reason, by encouraging people to come to their own conclusions by developing their own rational faculties; faith that, with proper encouragement and cultivation, people can learn to think for themselves, to form rational viewpoints, draw reasonable conclusions, think coherently and logically, persuade each other by reason and become reasonable persons, despite the deep-seated obstacles in the native character of the human mind and in society as we know it.

Fairmindedness: Having a consciousness of the need to treat all viewpoints alike, without reference to one’s own feelings or vested interests, or the feelings or vested interests of one’s friends, community or nation; implies adherence to intellectual standards without reference to one’s own advantage or the advantage of one’s group.

The Eight Intellectual Standards:

clarity, accuracy, precision, relevance, depth, breadth, logic, fairness.

NOTE: All text below is from the book “The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools (Thinker’s Guide Library)” by Richard Paul & Linda Elder.

Clarity: Recognize that thinking is always more or less clear. Assume that you do not fully understand a thought except to the extent that you can elaborate, illustrate, and exemplify it.

- Could you elaborate on what you are saying?

- I’m confused, can you clarify about “___?”

- Could you give me an example or illustration of your viewpoint?

- I hear you saying “___.” Am I hearing you correctly, or have I misunderstood you?

Accuracy: Recognize that thinking is always more or less accurate. Assume that you have not fully assessed it except to the extent that you have checked to determine whether it represents things as they REALLY are.

- How could we check to see if it is true?

- How could we verify the alleged facts?

- Can we trust the accuracy of the data given the questionable source from which they came?

Precision: Recognize that thinking is always more or less precise. Assume that you do not fully understand it except to the extent that you can specify it in detail.

- Could you give me more details about that?

- Could you be more specific?

- Could you specify your allegations or frustrations more fully?

Relevance: Recognize that thinking is always capable of straying from the task, question, problem, or issue under consideration. Assume that you have not fully assessed thinking except to the extent that you have ensured that all considerations used in addressing it are genuinely relevant to it.

- I don’t see how what you said bears on the question. Could you show me how it is relevant?

- Could you explain what you think the connection is between your question/viewpoint and the question/viewpoint we are discussing?

Depth: Recognize that thinking can either function at the surface of things or probe beneath the surface to deeper matters and issues. Assume that you have not fully assessed a line of thinking except to the extent that you have determined the depth required for the task at hand.

- Is this question simple or complex? Is it easy or difficult to answer?

- What makes this a complex question or problem?

- How are we dealing with the complexities inherent in the question?

Breadth: Recognize that thinking can be more or less broad-minded (or narrow minded) and that breadth of thinking requires the thinker to think insightfully within more than one point of view or frame of reference. Assume that you have not fully assessed a line of thinking except to the extent that you have determined how much breadth of thinking is required (and how much has in fact been exercised).

- What points of view are relevant to this issue?

- What relevant points of view have I ignored thus far?

- Am I failing to consider this issue from an opposing perspective because I am not open to changing my view?

- Have I entered the opposing views in good faith, or only enough to find flaws in them?

- I have looked at the question from an economic viewpoint. What is my ethical responsibility?

- I have considered a leftist position on the issue. What would a classical liberal say on the issue? What would a conservative say on the issue? A female view? A male view?

Logic: the parts make sense together, no contradictions; in keeping with the principles of sound judgment and reasonability. When one thinks, a person brings a variety of thoughts together into some order. When the combination of thoughts is mutually supporting and makes sense in combination, the thinking is logical. When the combination is not mutually supporting, it is contradictory or does not make sense, the combination is not logical. Thinking can be more or less logical. It can be consistent and integrated. It can make sense together or be contradictory or conflicting.

Questions that focus on logic include:

• Does all this fit together logically?

• Does this really make sense?

• Does that follow from what you said?

• Does what you say follow from the evidence?

• Before you implied this and now you are saying that, I don’t see how both can be true. What exactly is your position?

Fairness: free from bias, dishonesty, favoritism, selfish-interest, deception or injustice. Humans naturally think from a personal perspective, from a point of view that tends to privilege their position. Fairness implies the treating of all relevant viewpoints alike without reference to one’s own feelings or interests. Because everyone tends to be biased in favor of their own viewpoint, it is important to keep the intellectual standard of fairness at the forefront of thinking. This is especially important when the situation may call on us to examine things that are difficult to see or give something up we would rather hold onto. Thinking can be more or less fair. Whenever more than one point of view is relevant to the situation or in the context, the thinker is obligated to consider those relevant viewpoints in good faith. To determine the relevant points of view, look to the question at issue.

Questions that focus on fairness include:

• Does a particular group have some vested interest in this issue that causes them to distort other relevant viewpoints?

• Am I sympathetically representing the viewpoints of others?

• Is the problem addressed in a fair manner, or is personal vested interest interfering with considering the problem from alternative viewpoints?

• Are concepts being used justifiably (by this or that group)? Or is some group using concepts unfairly in order to manipulate (and thereby maintain power, control, etc.)?

• Are these laws justifiable and ethical, or do they violate someone’s rights?