I began writing this article back on July 31st, 2024 as I was starting to see a pattern of basic assumptions, attitudes, and behaviors that filtered into two major categories of relating to others, each having their own very distinct rules for playing, the “power over others game” and the “Logocentric truth game”. It was turning into quite a long article when my family and I had a massive collision with my wife’s ex husband in late August, who was playing the “power over others game” in every way imaginable, causing our family to experience a collision between the two forms of relating to reality. As it currently stands, one can indeed live a meaningful life with the Logocentric truth game, however, we personally found out the limits to how sustainable the truth game is in our current paradigm, since the power over others game is able to use arbitrary force of the macrocosm to crush truth in the microcosm and the macrocosm fairly easily. As of the writing of this article, my wife and I have pretty much lost everything dear to us, especially our family, but we were able to maintain our bond throughout the entire situation, even though the ex husband and the various government agencies involved did their best to drive a wedge between us in order to force my wife’s compliance with their arbitrary whims. With this in mind, I have decided to finish this article six months later, because I feel that people deserve to know the problems they will face the closer and closer to the truth that they become, but also the possibilities that they can experience when they choose to follow the truth in their lives.

The human quest for meaning and control has long been a battleground between competing worldviews, as Roger Scruton incisively noted in his observation that Marxism’s enduring appeal lies not in its truth but in the power it promises intellectuals to shape the world.

It is not the truth of Marxism that explains the willingness of intellectuals to believe it, but the power that it confers on intellectuals, in their attempts to control the world. And since, as Swift says, it is futile to reason someone out of a thing that he was not reasoned into, we can conclude that Marxism owes its remarkable power to survive every criticism to the fact that it is not a truth-directed, but a power-directed system of thought. ~”A Political Philosophy: Arguments for Conservatism” by Roger Scruton, 2006

This tension—between systems driven by power and those rooted in truth—echoes through the fabric of our personal and collective lives, manifesting in how we define ourselves, relate to others, and navigate societal structures. From the individual’s locus of identity to the grand machinations of governance, the choices we make between coercive dominance and rational authenticity determine not just our philosophies but the quality of our existence.

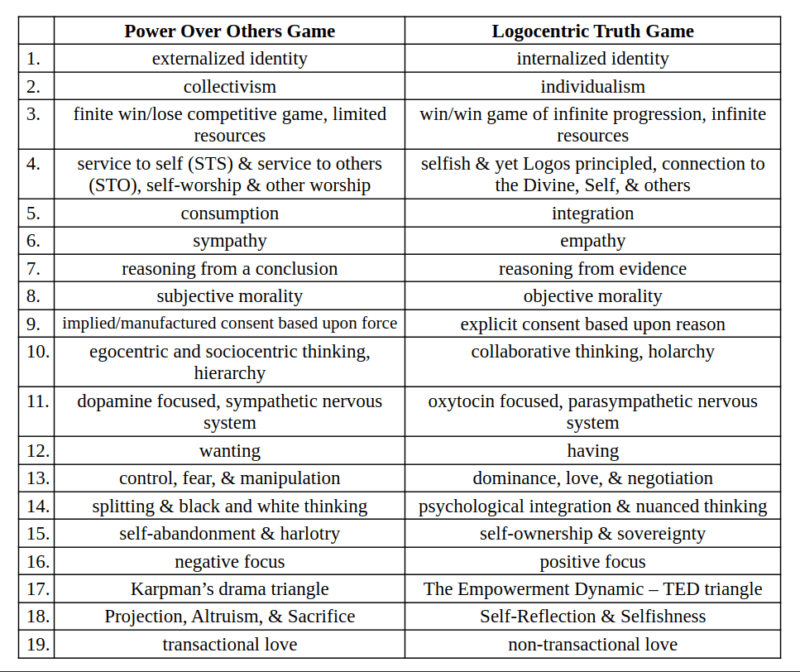

At the heart of this exploration lies a fundamental dichotomy: the “power over others game,” where control, manipulation, and external validation reign supreme, versus the “Logocentric truth game,” a pursuit of reason, self-awareness, and intrinsic worth that seeks harmony over hierarchy. These contrasting frameworks ripple through concepts like identity, morality, love, and law, revealing how our daily interactions—whether in families, workplaces, or nations—reflect either a scramble for supremacy or a collaborative dance toward understanding. This article delves into these dynamics, offering a tapestry of ideas that challenge the reader to reconsider what drives human behavior and how we might reclaim a life aligned with truth rather than tethered to power.

What follows is a journey through nineteen distinct yet interconnected lenses—from internal versus external loci of control to the stark divide between transactional and non-transactional love—each illuminating how the allure of power distorts our potential, while the pursuit of Logos offers a path to wholeness. Drawing on thinkers like Ayn Rand, Carl Jung, and John Locke, alongside psychological and philosophical insights, this piece invites reflection on how we might transcend the seductive pull of control and embrace a reality where meaning emerges not from subjugation but from the courage to reason and connect authentically. In a world increasingly shadowed by collectivist pressures and inverted laws, this narrative posits a radical yet practical vision for individuals and societies to flourish.

*Please see my Artificial Intelligence (AI) Disclaimer HERE, as it explains how I use AI in my articles.

1. External vs Internal Identity

People can either find their identity within themselves or outside of themselves, and this is called their “locus of control” or “locus of identity”. When external factors alone determine a person’s course of thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and outcomes, they are failing to take personal responsibility for their lives and are allowing external authorities (authors) to write their story for them. However, when internal factors shape their identity, especially through dedicated work and focus on upgrading one’s ability to reason, becoming a mature adult who is responsible for their thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and outcomes, and through developing their emotional intelligence, they stop blaming the outside world for everything wrong in their life, and rather own that they are the creator of their lives. Some quotes from Victor Frankl and Carl Jung come to mind, as does an article I wrote called “Locus of Identity and NPC Like ‘Spiritless Humans“. Also see my two questions to the Qwen2 AI chatbot on the topic of locus of control and identity below. Also see point #14 for self-ownership and sovereignty for the ultimate manner in demonstrating one’s internal locus of identity.

Q: What is the difference between an internal locus of control/identity and an external locus of control/identity?

A: An internal locus of control refers to the belief that one’s outcomes and identity are primarily shaped by personal choices, efforts, and intrinsic qualities, fostering a sense of agency and self-determination. Someone with an internal locus might attribute success to their hard work or view setbacks as opportunities to adapt, rooting their identity in self-defined values like resilience or competence—think of an entrepreneur who sees failure as a lesson they can master rather than a verdict from fate. This perspective ties identity to an inner compass, making it less swayed by external validation or criticism, and often aligns with self-reflection and accountability as drivers of personal growth.

Conversely, an external locus of control centers on the conviction that life’s events and one’s identity are largely dictated by outside forces—luck, other people, or circumstances—leading to a more reactive, dependent sense of self. A person with this outlook might credit a promotion to a boss’s favoritism or blame a breakup on their partner’s flaws, defining who they are through others’ actions or societal expectations, like someone who feels worthless without constant approval. This external anchoring makes identity fragile, tethered to shifting winds of opinion or fortune, and can fuel projection or victimhood as ways to cope with perceived powerlessness. The key difference lies in agency: internal locus builds identity from within, while external locus borrows it from without, shaping how each navigates control and responsibility.

~Grok 3

Q: Why is a locus of control sometimes called the locus of identity?

A: A locus of control is sometimes called the locus of identity because it fundamentally shapes how individuals perceive and construct who they are, linking their sense of self to either internal agency or external forces. When someone operates from an internal locus of control, they see their identity as a product of their own decisions, values, and efforts—say, a student who identifies as “capable” because they’ve worked hard to overcome obstacles. This internal anchor ties their self-concept to their ability to influence outcomes, making locus of control a blueprint for identity: they are what they choose to become, rooted in self-directed authorship rather than outside judgment. The term “locus of identity” thus reflects this deep connection, where control over one’s life narrative becomes the core of who they believe they are.

On the flip side, an external locus of control earns the “locus of identity” label because it positions identity as something bestowed or dictated by external circumstances, other people, or chance, effectively outsourcing self-definition. For instance, someone might identify as a “failure” because they believe society or bad luck has stacked the deck against them, their sense of self hinging on what they can’t control rather than what they can. This external orientation means their identity shifts with the tides of approval, rejection, or fate, making locus of control synonymous with identity’s origin point—outside themselves. The phrase captures this interplay: whether control is internal or external, it locates the source of identity, determining whether one’s “I am” is self-crafted or externally imposed.

~Grok 3

Q: Please explain “self-determination”.

A: Self-determination is the ability and process by which individuals take control of their own lives, making choices and pursuing goals based on their personal values, desires, and intrinsic motivations rather than external pressures or dictates. It reflects a strong internal locus of control, where a person believes they can shape their destiny through effort and decisions—think of an artist who forges a unique path despite societal expectations, driven by their own vision. Rooted in autonomy, competence, and relatedness (per self-determination theory), it’s about acting with agency, whether that’s choosing a career, setting boundaries, or defining one’s identity, and it often intertwines with self-reflection to ensure those choices align with an authentic sense of self.

Quotes from Carl Jung and Viktor Frankl on taking responsibility for one’s internal world and responses regardless of external circumstances:

If you imagine someone who is brave enough to withdraw all his projections, then you get an individual who is conscious of a pretty thick shadow. Such a man has saddled himself with new problems and conflicts. He has become a serious problem to himself, as he is now unable to say that they do this or that, they are wrong, and they must be fought against… Such a man knows that whatever is wrong in the world is in himself, and if he only learns to deal with his own shadow he has done something real for the world. He has succeeded in shouldering at least an infinitesimal part of the gigantic, unsolved social problems of our day.

~Carl Jung, “Psychology and Religion” (1938). In CW 11: Psychology and Religion: West and East. P.140

Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way. ~Viktor E. Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning

When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves. ~Viktor E. Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning

The one thing you can’t take away from me is the way I choose to respond to what you do to me. The last of one’s freedoms is to choose one’s attitude in any given circumstance. ~Viktor E. Frankl

In my experience an internal locus of identity is associated with the Logocentric truth game in that those who exercise self-directed lives are not focused on controlling others, and really don’t appreciate being controlled, and they’re not going to act like a victim even if and when external forces or people attempt to control them. However, those with an external locus of control are always seeking somebody else to blame for their problems, are easily manipulated by external people and forces, and are constantly fighting for supremacy in a dog-eat-dog world of power over others.

2. Collectivism vs Individualism

Q: What is collectivism, what is individualism, and how might collectivism be connected to the “power over others game” and individualism be connected to the “Logocentric truth game”? How would collectivism be related to an externalized locus of control/identity, and how would individualism be more related to having an internalized locus of control/identity?

A: Collectivism is a social and philosophical framework that prioritizes the group—whether family, community, or society—over the individual, emphasizing shared goals, interdependence, and collective well-being as the basis for identity and action. It values harmony, cooperation, and often sacrifice for the common good, as seen in cultures where familial duty or national loyalty shapes one’s role and worth—think of a village rallying to support a struggling member, where the “we” supersedes the “I.” Individualism, conversely, centers on the primacy of the individual, championing personal freedom, self-reliance, and the pursuit of one’s own goals and identity, often regardless of group expectations. It’s exemplified by someone forging a unique path, like an inventor breaking from tradition to follow their vision, where personal agency and self-expression define value.

Collectivism can connect to the “power over others game” when its ideals are co-opted by manipulators to enforce conformity and control, leveraging the group’s authority to suppress dissent or demand loyalty. A leader might exploit collective identity—say, “we’re all in this together”—to project their own flaws onto outsiders (e.g., scapegoating a rival faction) or guilt-trip individuals into altruistic sacrifice for “the cause,” consolidating power by making the group’s will paramount. This dynamic thrives in environments where questioning the collective is taboo, as seen in authoritarian regimes that use propaganda to align personal worth with group obedience. Here, collectivism becomes a tool for dominance, bending individuals to serve a hierarchical “us” rather than a mutual good. Individualism, by contrast, aligns with the “logocentric truth game” because it prioritizes self-directed reason and authenticity, encouraging people to reflect critically and seek truth through personal inquiry rather than group consensus—think of a philosopher challenging societal norms to uncover deeper principles, rooted in logos over collective narrative.

The link between collectivism and an externalized locus of control/identity lies in how it often ties one’s sense of self to the group’s approval, status, or needs, making identity contingent on external validation rather than internal conviction. In a collectivist setting, someone might define themselves as a “good citizen” only if the community affirms it, or feel powerless against the group’s decisions—like a worker in a rigid hierarchy who attributes their fate to the system rather than their own choices. This external locus shifts agency outward, fostering dependency on collective judgment or fate, which can make individuals more susceptible to manipulation by those wielding group authority. Collectivism’s emphasis on interdependence can thus blur personal boundaries, anchoring identity in what “they” think or demand rather than what “I” determine.

Individualism, meanwhile, relates to an internalized locus of control/identity by grounding self-worth and direction in personal agency, where one’s choices and reasoning shape who they are and what they achieve. An individualist might see a setback as a personal challenge to overcome through effort—like an athlete training harder after a loss—defining themselves by their resilience rather than others’ opinions. This internal locus fosters self-determination, as identity emerges from within, sculpted by self-reflection and rational assessment rather than external forces. By valuing autonomy over conformity, individualism supports a logocentric pursuit of truth, where the individual’s mind, not the crowd’s voice, becomes the arbiter of reality, reinforcing a self-crafted identity resilient to outside sway.

~Grok 3

Individualism regards man—every man—as an independent, sovereign entity who possesses an inalienable right to his own life, a right derived from his nature as a rational being. Individualism holds that a civilized society, or any form of association, cooperation or peaceful coexistence among men, can be achieved only on the basis of the recognition of individual rights—and that a group, as such, has no rights other than the individual rights of its members. ~Ayn Rand, The Virtue of Selfishness, Chapter on Racism

Do not make the mistake of the ignorant who think that an individualist is a man who says: “I’ll do as I please at everybody else’s expense.” An individualist is a man who recognizes the inalienable individual rights of man—his own and those of others.

An individualist is a man who says: “I will not run anyone’s life—nor let anyone run mine. I will not rule nor be ruled. I will not be a master nor a slave. I will not sacrifice myself to anyone—nor sacrifice anyone to myself.”

~Ayn Rand, “Textbook of Americanism,” The Ayn Rand Column

The mind is an attribute of the individual. There is no such thing as a collective brain. There is no such thing as a collective thought. An agreement reached by a group of men is only a compromise or an average drawn upon many individual thoughts. It is a secondary consequence. The primary act—the process of reason—must be performed by each man alone. We can divide a meal among many men. We cannot digest it in a collective stomach. No man can use his lungs to breathe for another man. No man can use his brain to think for another. All the functions of body and spirit are private. They cannot be shared or transferred. ~Ayn Rand, “The Soul of an Individualist,” For the New Intellectual

3. Finite Win/Lose Competitive Game, Limited Resources vs Win/Win Game of Infinite progression, Infinite Resources

Q: Please explain the differences between Simon Sinek’s concept of “the two games”, the competitive game and the infinite game.

A: Simon Sinek’s concept of “the two games” distinguishes between the finite game and the infinite game, based on their rules, objectives, and mindsets, drawing from James Carse’s philosophical framework. The finite game is competitive, with fixed rules, known players, and a clear endpoint—its goal is to win by outranking others within a defined timeframe, like a sports match or a corporate sales quarter where one team emerges victorious. Players focus on short-term gains, often prioritizing outcomes over process, and success is measured by tangible results—think of a company racing to dominate market share, caring more about beating rivals than sustaining long-term value. It’s a zero-sum setup: for one to win, others must lose, driving a mindset of scarcity and rivalry.

The infinite game, by contrast, has no fixed endpoint or ultimate winner; it’s about perpetuating play, adapting, and enduring beyond immediate victories, with rules and players that can shift over time. The objective isn’t to “win” but to keep the game going—think of a business innovating to stay relevant across decades or a leader fostering a vision that outlives their tenure. Success here lies in resilience and purpose, not domination, as seen in organizations that prioritize culture and adaptability over quarterly triumphs. Unlike the finite game’s focus on competition and closure, the infinite game aligns with a process-oriented, collaborative ethos, where the aim is to contribute to something larger, embracing change and viewing setbacks as part of an ongoing journey rather than final defeats.

~Grok 3

Q: Please define game theory.

A: Game theory is a mathematical and strategic framework for analyzing situations where multiple players make decisions that influence one another’s outcomes, focusing on how rational choices, interdependencies, and incentives shape cooperation or competition. It models scenarios—ranging from economics to politics to biology—as “games” with defined rules, players, and payoffs, exploring how individuals or groups optimize their strategies, whether in zero-sum contexts (where one’s gain is another’s loss) or non-zero-sum settings (where mutual benefit is possible). Developed by thinkers like John von Neumann and John Nash, it uses concepts like Nash equilibrium—where no player can improve their outcome by unilaterally changing strategy—to predict behavior, offering insights into conflict, negotiation, and resource allocation in both finite and infinite contexts. ~Grok 3

Q: Please define a zero-

sum game.

A: A zero-sum game, in game theory, is a competitive scenario where resources or benefits are fixed, and one player’s gain directly equals another’s loss, resulting in a net outcome of zero when all gains and losses are summed. Imagine a poker game with a set pot: if one player wins $100, others collectively lose $100, with no new value created. Defined by strict opposition, such games assume limited stakes—like market share in a saturated industry—where success requires outmaneuvering opponents, often through strategies like bluffing or sacrifice, making cooperation irrelevant since the pie can’t grow. It’s a finite framework where winning is absolute, contrasting with non-zero-sum games where mutual benefit can expand the total outcome. ~Grok 3

Q: Please explain how Simon Sinek’s finite Win/Lose competitive game and game theory’s zero sum game with limited resources might be connected to the “power over others game”, and how his concept of the Win/Win game of infinite progression and game theory’s infinite Resources might be connected to the “Logocentric truth game”.

A: Simon Sinek’s finite “Win/Lose” competitive game aligns closely with game theory’s zero-sum game, where limited resources mean one player’s gain is another’s loss, and this dynamic connects directly to the “power over others game” through its emphasis on dominance and control. In Sinek’s finite game, the focus is on achieving a definitive victory within set boundaries—like a corporation racing to outpace a rival in quarterly profits—mirroring the zero-sum premise where resources (market share, prestige, influence) are finite, and success requires someone else’s defeat. This setup fuels the power-over-others game, as players might use tactics like psychological projection (blaming competitors for their own flaws) or enforced sacrifice (pushing employees to overwork) to secure an edge. The finite, zero-sum mindset breeds a hierarchical struggle where power is wielded to suppress or outperform others, prioritizing outcomes over ethics or collaboration—think of a politician smearing an opponent to win an election, caring only for the trophy of victory.

In contrast, Sinek’s infinite “Win/Win” game of progression, where the goal is to keep playing and improving without a fixed end, parallels game theory’s concept of infinite resources, where value can expand through creativity and cooperation, linking to the “logocentric truth game” via its focus on process and reason. In the infinite game, success isn’t about beating others but sustaining a vision—like a company innovating for long-term relevance rather than short-term dominance—echoing the idea that resources (ideas, knowledge, relationships) aren’t capped but grow through shared effort. This resonates with the logocentric pursuit of truth, where self-reflection and rational inquiry drive progress, not rivalry; a scientist refining a theory over decades, open to collaboration, exemplifies this, valuing discovery over conquest. The infinite, resource-expanding approach rejects power-over-others tactics, instead fostering a truth-seeking ethos where all can advance through mutual learning.

The connection deepens when considering how each game shapes identity and control: the finite/zero-sum framework ties to an external locus, where worth hinges on beating others for scarce rewards, while the infinite/infinite-resources model supports an internal locus, rooting identity in personal growth and contribution. In the power-over-others game, a finite player might manipulate perception (e.g., projecting weakness onto a rival) to hoard limited influence, their identity fragile without victory—akin to a dictator clinging to power through division. Conversely, the logocentric truth game thrives in Sinek’s infinite frame, where infinite resources like insight or resilience fuel a process-oriented life; a leader who admits mistakes and adapts strengthens their team’s trust, their identity secure in reason, not rank. Thus, the finite game’s competitive scarcity drives control through subjugation, while the infinite game’s expansive potential aligns with truth through autonomy and shared evolution.

~Grok 3

4. Service to Self (STS) & Service to Others (STO), Self-Worship & Other Worship vs Selfish & yet Logos Principled, connection to the Divine, Self, & Others

Service to Self (STS) and Service to Others (STO) are a concept first established in the “Ra Material”, which were channelings of a so-called ‘soul collective’ named “Ra”, which you can find HERE. As mentioned earlier, I believe the two categories to be a false dichotomy/dilemma logical fallacy that could either be well intentioned misinformation, but could also be deliberate disinformation that was used to confuse the two true categories of beings that I am covering in this current article, those playing the “power over others game” and the “Logocentric truth game“. Basically, STS is when a being is “selfish” and is considered evil, but as I’ve written before based upon the insights of Ayn Rand that selfishness in its purest form can be seen as a virtue, and STO is when a being is altruistic and is therefore considered good and moral, but I’ve also covered that based upon Ayn Rand’s writings, stating that it is an error to consider a human a sacrificial animal where their sole existence is to serve others in a selfless manner; after all, we’re here on Earth to develop our Self and not lose our Self. So it is a false dilemma logical fallacy because it fails to consider other possibilities, and gives us two bad options to choose from.

The false dilemma fallacy, also known as a false dichotomy, is a logical error where a situation is presented as having only two mutually exclusive options—often an “either/or” choice—when in reality, additional alternatives or a spectrum of possibilities exist. For example, claiming “you’re either with us or against us” ignores the possibility of neutrality or partial support, oversimplifying complex issues into a binary trap. This fallacy manipulates reasoning by excluding middle ground or nuanced solutions, often used rhetorically to force agreement or polarize opinions, and it fails under scrutiny when the hidden options—like compromise or a third path—are revealed. It distorts truth by framing decisions as more limited than they are, undermining rational deliberation. ~Grok 3

Ayn Rand on Altruism:

What is the moral code of altruism? The basic principle of altruism is that man has no right to exist for his own sake, that service to others (STO) is the only justification of his existence, and that self-sacrifice is his highest moral duty, virtue and value.

Do not confuse altruism with kindness, good will or respect for the rights of others. These are not primaries, but consequences, which, in fact, altruism makes impossible. The irreducible primary of altruism, the basic absolute, is self-sacrifice—which means; self-immolation, self-abnegation, self-denial, self-destruction—which means: the self as a standard of evil, the selfless as a standard of the good.

Do not hide behind such superficialities as whether you should or should not give a dime to a beggar. That is not the issue. The issue is whether you do or do not have the right to exist without giving him that dime. The issue is whether you must keep buying your life, dime by dime, from any beggar who might choose to approach you. The issue is whether the need of others is the first mortgage on your life and the moral purpose of your existence. The issue is whether man is to be regarded as a sacrificial animal. Any man of self-esteem will answer: “No.” Altruism says: “Yes.””

~Ayn Rand

The STO vs STS categories are both associated with the drama triangle in point #16, as well as the need for personality worship. Personality worship is when one party desires adoration and attention from another, and it is based in the personality traits of narcissism. In order for one party to be worshiped on a pedestal though, another party must be the one who worships them to be below them, and to worship a personality, even in Divine form, is wrong, because it is considered idolatry. We can respect and honor the truth within each other, and definitely respect and honor the truth within a being who has fully aligned themselves to the point of full Selfhood, such as Jesus did, but at least from my experience, the logical conclusion of personality worship in my own life and relationships hasn’t allowed for true union with the Divine or each other, as I have found that it is dopamine based and not oxytocin based, and can lead to resentment/envy and/or betrayal rather than lasting connection. Examples of idolatry in relationships are idolizing a company, a famous personality such as a musician, actor, CEO, YouTube /Tik Tok personality, politician, or even your partner or crush.

Don’t ever attach yourself to a person, place, company, or project. Attach yourself to a mission, a calling, and a purpose ONLY. That’s how you keep your power and peace. ~@missewell

It is clear how putting another personality on a pedestal above oneself to worship them is idolatrous, as it is putting that personality as equal to or greater than the Divine and Logos, and it also creates a power imbalance where the worshiped is clearly more powerful and above the ones worshiping them. As a result of the power imbalance, the worshiped personality can easily manipulate and twist those under them to do immoral acts, and to act out of alignment with their own higher good and self-interests, which is why this is clearly the power over others game.

In contrast to the false dichotomy of STO vs STS, we have the concept of “principled selfishness“, which is selfishness that acknowledges the presence of others, and respects their rights as much as it respects its own rights, and does this due to its own foundation being the principles of Logos, such as the eight intellectual character traits, the eight universal intellectual standards, the principles of natural law (which can be found by reading the works of John Locke and St Thomas Aquinas), using the Trivium method in an internalized manner, and making one’s internal emotional states consistent and aligned with empathetic reason.

Ayn Rand on selfishness:

The meaning ascribed in popular usage to the word “selfishness” is not merely wrong: it represents a devastating intellectual “package-deal,” which is responsible, more than any other single factor, for the arrested moral development of mankind.

In popular usage, the word “selfishness” is a synonym of evil; the image it conjures is of a murderous brute who tramples over piles of corpses to achieve his own ends, who cares for no living being and pursues nothing but the gratification of the mindless whims of any immediate moment.

Yet the exact meaning and dictionary definition of the word “selfishness” is: concern with one’s own interests.

This concept does not include a moral evaluation; it does not tell us whether concern with one’s own interests is good or evil; nor does it tell us what constitutes man’s actual interests. It is the task of ethics to answer such questions.

~Ayn Rand, “The Virtue of Selfishness”

Do not make the mistake of the ignorant who think that an individualist is a man who says: “I’ll do as I please at everybody else’s expense.” An individualist is a man who recognizes the inalienable individual rights of man—his own and those of others.

An individualist is a man who says: “I will not run anyone’s life—nor let anyone run mine. I will not rule nor be ruled. I will not be a master nor a slave. I will not sacrifice myself to anyone—nor sacrifice anyone to myself.”

~Ayn Rand, “Textbook of Americanism,” The Ayn Rand Column

5. Consumption vs Integration

Q: Psychologically speaking, please give a three paragraph response discussing the distinctions between how a narcissist “consumes” the energy of their prey in an enmeshed manner, and the opposite healthy alternative of how somebody might integrate positive character traits from another without “eating” them.

A: Psychologically, a narcissist “consumes” the energy of their prey in an enmeshed manner by parasitically feeding off their victim’s emotional, mental, or even physical resources to bolster their own fragile ego, often leaving the prey depleted and identity-eroded. This process is rooted in the narcissist’s inability to sustain self-worth internally; they project their insecurities outward and latch onto others—spouses, children, or colleagues—as sources of validation, admiration, or control. Through tactics like gaslighting, guilt-tripping, or idealization-devaluation cycles, they entangle their prey in a web of dependency, “eating” their vitality by demanding constant attention or sacrifice—think of a narcissistic parent who thrives on a child’s achievements while dismissing their autonomy, draining the child’s sense of self to fuel the parent’s grandiosity. This enmeshment blurs boundaries, turning the prey into an extension of the narcissist rather than a separate entity, a dynamic marked by exploitation rather than mutual growth.

In contrast, a healthy individual integrates positive character traits from another through admiration and inspiration, not consumption, preserving both parties’ autonomy while fostering personal development. Rather than “eating” someone’s energy, they observe qualities—like a friend’s resilience or a mentor’s patience—and consciously choose to emulate them, adapting these traits to fit their own identity without diminishing the source. For instance, someone might admire a coworker’s confidence in meetings, reflect on how it aligns with their own goals, and practice it themselves, all while respecting the coworker’s distinctiveness. This process is additive, not extractive; it builds on mutual respect and an internal locus of control, where growth comes from self-directed effort rather than leaching off another’s essence, maintaining clear boundaries between self and other.

The distinction lies in intent and outcome: the narcissist’s enmeshed consumption is a zero-sum game, driven by a need to dominate and fill an inner void, whereas healthy integration reflects an infinite game of self-betterment that honors both parties. The narcissist’s prey often emerges hollowed out, their energy siphoned to prop up an insatiable ego—like a partner left exhausted by endless demands for affirmation—while the healthy alternative leaves both individuals intact and enriched, as seen when two friends inspire each other’s courage without losing their individuality. The narcissist’s approach collapses under its own weight, breeding resentment and disconnection, while healthy emulation thrives on reciprocity and authenticity, aligning with self-reflection rather than projection. Ultimately, one destroys through entanglement; the other elevates through independence, highlighting a core psychological divide between parasitic control and genuine growth.

~Grok 3

Q: How might consumption be related to the “power over others game” and integration be related to the “Logocentric truth game”?

A: Consumption, as a psychological and behavioral stance, aligns with the “power over others game” because it involves extracting resources—emotional, physical, or social—from others to assert dominance or bolster one’s own position, reflecting a finite, zero-sum mindset where one’s gain requires another’s loss. In this game, a narcissist or manipulative entity “consumes” their target’s energy, time, or identity—like a boss who drains employees with unrelenting demands to secure personal success—using tactics such as projection or enforced sacrifice to maintain control. This approach thrives on external validation and scarcity, treating others as means to an end rather than ends in themselves, and prioritizes winning (power) over process or mutual benefit, mirroring the competitive ethos of Sinek’s finite game where the goal is to outrank rather than coexist.

Integration, conversely, connects to the “logocentric truth game” by emphasizing a process-oriented, rational pursuit of growth that draws inspiration from others without diminishing them, aligning with an infinite, truth-seeking framework rooted in self-awareness and reason. Rather than consuming, a person integrates positive traits—say, adopting a peer’s discipline through reflection and practice—building their own character while respecting the source, as in an infinite game where resources like wisdom or resilience expand through shared influence. This reflects an internal locus of control, where identity and progress stem from self-directed effort, not exploitation, and embodies logos by valuing authenticity and understanding over dominance. Unlike consumption’s parasitic grip, integration fosters autonomy and reciprocity, contributing to a collective journey of enlightenment rather than a battle for supremacy.~Grok 3

From a spiritual perspective, Michael Topper wrote the following, and he did so from the STO vs STS false dilemma, however, this part still remains quite true and compelling regardless of what I consider a false underlying assumption:

The […][negative] way of achieving “density of consciousness” is to “gain weight” by assimilation of other consciousness units. This is generally promoted as “All is One” and refers to “evil” as a “rebellion” or a fault or something that will ultimately be “done away with.”

[…][The positive], on the other hand sees “gaining weight” in a different way. It sees that an acknowledgement of the consciousness of “other self” as equal to its own consciousness, in spite of completely different manifestation of that being, is the way to “network” the consciousness so that the Whole is greater than the sum of the parts.

The difference is that the [positive] guys recognize consciousness as being an “integrative” activity of mutual networking and interdependence because they view all others as self, even if they are different, and therefore seek to help and assist because the other IS self in an absolute internal sense. In this way, Absolute Consciousness, or God is “glorified” by a marvelous diversity of being if you wish to put it in those terms.

The negative guys, on the other hand, play the game in terms of domination, subjugation and absorption of other consciousnesses into “One.” . But, they too, understand that the rules of the game posit that in order for them to truly “absorb” into their being these other “consciousnesses,” that the “other” must choose to become part of their “self-aggrandizement.”

An unwilling “food” is, in essence, not “nutritious” so to say. If the consciousness does not choose, it becomes a “poison” to the consciousness that seeks to “eat it.” And so they must promote “Oneness” in a very particular way.

Note that both sides acknowledge “Oneness,” but in very different ways. [Oneness through the integration of personality traits (4D individuality/5D unity) vs Oneness through the assimilation of personalities/individuals (conformity 3D/individuality negative 4D).]

~Michael Topper, “The Positive/Negative Realms of Higher Densities”, 1994

6. Sympathy vs Empathy

“We don’t know enough to make judgments. That statement embodies the heart and soul of empathy. The core of empathy is understanding, and understanding always precedes explanation in the effort to understand, empathy asks questions and refuses quick answers. “I don’t know” is one of empathy’s most powerful statements. From that admission of not having all the answers, empathy starts searching for ways to expand the picture in order to develop a broader understanding.” ~Arthur P. Ciaramicoli, Ed.D., Ph.D, “The Power of Empathy (affiliate link)”

Intellectual Empathy: Having a consciousness of the need to imaginatively put oneself in the place of others in order to genuinely understand them, which requires the consciousness of our egocentric tendency to identify truth with our immediate perceptions of long-standing thought or belief. This trait correlates with the ability to reconstruct accurately the viewpoints and reasoning of others and to reason from premises, assumptions, and ideas other than our own. This trait also correlates with the willingness to remember occasions when we were wrong in the past despite an intense conviction that we were right, and with the ability to imagine our being similarly deceived in a case-at-hand. ~Richard Paul & Linda Elder, “The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools” (affiliate link)“

Q: What is the difference between sympathy and empathy? Please use etymology to further Distinguish the two.

A: Sympathy and empathy diverge in their emotional engagement and perspective, with sympathy being a feeling for someone’s distress—often pity or sorrow from a distance—while empathy involves a deeper, participatory understanding with them, as captured in the quotes you provided. Sympathy might manifest as comforting a grieving friend with kind words, acknowledging their pain without fully entering it, maintaining an external stance of care. Empathy, per Arthur Ciaramicoli’s definition, starts with “I don’t know” and seeks to “expand the picture” of another’s experience, asking questions to genuinely grasp their reality—like sitting with that friend and imagining their loss as if it were your own. Similarly, Richard Paul and Linda Elder’s “intellectual empathy” demands imaginatively inhabiting another’s viewpoint, reconstructing their reasoning despite one’s own biases, a step beyond sympathy’s surface-level concern.

Etymologically, these differences crystallize. “Sympathy” stems from the Greek sympatheia—syn- (“with”) and pathos (“feeling”)—originally meaning “fellow feeling,” suggesting a shared emotion but one that evolved into a more detached resonance, like standing alongside someone in their suffering. “Empathy,” coined from the German Einfühlung (“feeling into”), blends Greek en- (“in”) and pathos, literally “in feeling,” reflecting its roots in projecting oneself into another’s experience, a term adapted from aesthetics to psychology in the early 20th century. While sympatheia aligns with a companionate but separate sorrow, Einfühlung’s inward thrust matches Ciaramicoli’s exploratory humility and Paul and Elder’s imaginative leap into another’s mind, highlighting empathy’s immersive nature.

The quotes amplify this contrast: sympathy observes and reacts, while empathy, as Ciaramicoli frames it, refuses quick judgments and searches for broader understanding, and as Paul and Elder describe, actively counters egocentrism to reason from another’s premises. Sympathy might say, “I’m sorry you’re hurting,” staying outside the emotional frame; empathy, embracing “I don’t know” or a willingness to recall personal error, dives in to feel and think alongside the other, bridging the gap between selves. Etymology underscores this—sympathy as a “with” that parallels, empathy as an “in” that inhabits—making sympathy a supportive echo and empathy a profound, truth-seeking connection that demands vulnerability and curiosity.

~Grok 3

Here’s my own take on the topic. Most people hold a different definition of empathy than I do. Their version of empathy is how I define sympathy, and sympathy definitely needs to be held in check, because it’s typically psychologically enmeshed “together with the feeling”, which is the etymological breakdown of sympathy.

Empathy:

-en (in) + pathos (feeling)

Sympathy:

syn- (together) + pathos (feeling)

Whereas sympathy is being enmeshed together with others in a feeling, and only understands the other based upon a shared feeling with them, empathy seeks to understand others by exploring the feeling using reason and other reason based processes. It might be argued that sympathy is the underdeveloped, boundaryless, and unconscious version of empathy, while empathy is a character trait that we are able to consciously develop within ourselves that seeks to gain understanding, but it does so in an interpersonal manner, rather than regular logic which is examining things and processes in a more common external manner. I call empathy the emotional component of reason/logic, and coined the term “empathetic reasoning” to describe how empathy is used in conjunction with logic to gain understanding of self and others.

Psychological enmeshment is a relational dynamic where boundaries between individuals blur, leading to an unhealthy fusion of emotions, identities, or responsibilities, often at the expense of personal autonomy. It occurs when one person’s sense of self becomes overly intertwined with another’s, such as a parent living vicariously through a child, diminishing both parties’ ability to function independently. ~Grok 3

Psychological boundaries are the invisible lines that define an individual’s emotional, mental, and relational space, clarifying where one person’s identity and responsibilities end and another’s begin, much like a fence between backyards determines which homeowner maintains their respective land. They establish who is accountable for what—such as one person owning their feelings versus expecting another to fix them—promoting autonomy and healthy differentiation in relationships. ~Grok 3

Q: Please explain how sympathy might be more psychologically enmeshed while empathy might be more psychologically boundaried and differentiated. Also please explain how sympathy might be more geared towards the “power over others game” and how empathy might be more geared towards the “Logocentric truth game”.

A: Sympathy might be more psychologically enmeshed because it often involves an emotional merging with another’s distress without fully distinguishing between self and other, leading to a blurred sense of identity that can feel overwhelming or clingy. When someone sympathizes—say, crying alongside a friend over their breakup—they may absorb the other’s pain as if it’s their own, losing sight of where their feelings end and the friend’s begin, which aligns with enmeshment’s lack of clear boundaries. This fusion can stem from a desire to “fix” or rescue, projecting one’s own need to be needed onto the sufferer, rather than maintaining a separate perspective. While well-intentioned, this entanglement risks over-identification, where the sympathizer’s emotional state becomes contingent on the other’s, eroding personal autonomy in a way that empathy avoids.

Empathy, by contrast, might be more psychologically boundaried and differentiated because it involves understanding another’s experience while retaining a distinct sense of self, fostering connection without losing individuality. Per Ciaramicoli’s view, empathy starts with “I don’t know” and seeks to expand understanding, and per Paul and Elder, it imaginatively enters another’s viewpoint—both requiring a conscious step into the other’s shoes without merging identities. For instance, an empathic listener might feel a friend’s breakup pain, imagining their perspective, yet remain grounded enough to offer clarity rather than drown in shared sorrow. This differentiation preserves boundaries, allowing empathy to be a bridge rather than a takeover, supporting mutual respect and personal integrity over emotional fusion.

In the “power over others game,” sympathy’s enmeshment can serve manipulation, as its blurred boundaries make it ripe for control tactics, whereas empathy’s boundaried nature aligns with the “logocentric truth game” by prioritizing reason and authenticity. Sympathy might fuel power plays when a manipulator feigns pity—think of a narcissist “sympathizing” with a target’s struggles to gain trust, only to exploit their vulnerability—using emotional entanglement to obligate or guilt-trip, fitting the finite game’s win/lose ethos where one’s gain (control) is another’s loss. Empathy, however, supports the infinite, truth-seeking game: its focus on understanding (Ciaramicoli) and countering egocentrism (Paul and Elder) rejects domination for a process of mutual growth—like a leader empathizing with a team’s challenges to build trust, not leverage. Thus, sympathy’s enmeshed tilt can bend toward power-over-others, while empathy’s differentiated stance fosters logos-driven truth and connection.

~Grok 3

One concept that often gets confused with empathy is compassion; whereas compassion is acting upon the understanding that was gained through empathetic processes, how most people actually perform compassionate actions is based upon enmeshed sympathetic processes that lack understanding. Sympathetic compassion is therefore more akin to do-gooding by moral busybodies, while empathetic compassion would then be the most reasonable and moral action for the well-being of ourselves and those around us, because it results from reason based understanding, and not from enmeshed understanding.

On the dangers of people do-gooding from sympathy and blind compassion, and how it can be used to support tyranny, CS Lewis had this to say:

Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for all the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It would be better to live under robber barons than under omnipotent moral busybodies. The robber baron’s cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience.

~C.S. Lewis

Q: How might the idea of “do-gooding” be related to sympathy and compassion, and lack empathy and boundaries? How can do-gooders be dangerous, all the while thinking they are helping and doing good for people and society?

A: “Do-gooding” often aligns with sympathy and compassion rather than empathy and boundaries because it tends to prioritize feeling for others and acting on a desire to alleviate their suffering, without necessarily understanding their true needs or maintaining personal separation. Sympathy drives the do-gooder to pity a struggling community—say, rushing to “save” them with unsolicited aid—while compassion fuels a broad, heartfelt urge to help, but both can skip empathy’s deeper step of asking questions to grasp the other’s perspective, as Ciaramicoli suggests. This lack of empathy, paired with weak boundaries, leads to enmeshment: the do-gooder might assume responsibility for others’ problems, like a homeowner tending a neighbor’s yard unasked, projecting their own values or savior complex onto the situation. Without boundaries to define who owns what—be it emotions, decisions, or outcomes—the do-gooder risks overstepping, driven by a sympathetic impulse rather than a differentiated, empathic connection.

The danger of do-gooders lies in this well-intentioned overreach, as their lack of empathy and boundaries can harm rather than help, all while they believe they’re benefiting people and society. By not pausing to understand—like flooding a village with food they can’t store, ignoring local systems—they may undermine autonomy, create dependency, or impose solutions that clash with cultural realities, much like a parent “fixing” a child’s life without their input stunts growth. This ties to the “power over others game”: their “help” can subtly dominate, reinforcing their self-image as benevolent while disempowering recipients, as seen in historical missionary efforts that erased traditions under the guise of salvation. Convinced of their goodness, do-gooders may dismiss feedback or unintended harm, their lack of self-reflection blinding them to how their sympathy-driven actions, absent empathic boundaries, can perpetuate control rather than foster true progress.

~Grok 3

This next question is personal to our situation, but it underscores the dangers of do-gooding and how it can destroy the lives it pretends to defend and protect. It’s an emotional projection of sorts, where do-gooders project their own victim mentality onto the party their own inner child most relates to, and punishes the other side, regardless of the truth, and often regardless of the consequences to the various innocent parties; they don’t seek to assist, gently correct, and grow, but to punish and force conformity to their shallow views.

Q: What dangers could family law systems pose to families if they are filled with sympathetic do-gooders rather than rationally minded, empathetic, and boundaried individuals?

A: Family law systems staffed with sympathetic do-gooders—those driven by pity and a desire to “rescue” rather than rational empathy and clear boundaries—pose significant dangers by prioritizing emotional impulses over fair, reasoned outcomes, potentially destabilizing families. A sympathetic judge or social worker might see a tearful parent’s plea as a call to “save” them, rushing to grant custody or support without delving into the child’s needs or the other parent’s perspective, lacking the empathic depth to ask questions and understand the full picture. This enmeshed approach blurs boundaries, as they take on responsibility for “fixing” perceived victims—much like tending someone else’s yard—rather than respecting each party’s agency and accountability. Such decisions, fueled by a savior complex instead of evidence or balanced inquiry, risk favoring the loudest sob story, like a narcissist feigning vulnerability, over the family’s long-term stability.

The absence of rational, empathic, and boundaried individuals in these systems can amplify harm by enabling manipulation and eroding trust, turning legal processes into tools of control rather than justice. Without empathy’s focus on understanding—like reconstructing viewpoints per Paul and Elder—do-gooders might overlook a healthy parent’s contributions, swayed instead by sympathetic bias toward a “suffering” party, inadvertently supporting power-over-others dynamics where one wins at another’s expense. Unclear boundaries further muddy responsibility: a do-gooder might over-intervene, stripping parents of autonomy with excessive oversight, or under-intervene, leaving kids vulnerable by assuming “help” is enough. This contrasts with a boundaried, empathic system that discerningly assigns accountability—e.g., ensuring a child’s safety without infantilizing parents—preserving family integrity through truth-seeking rather than knee-jerk compassion, which can fracture relationships and perpetuate dependency under the guise of care.

~Grok 3

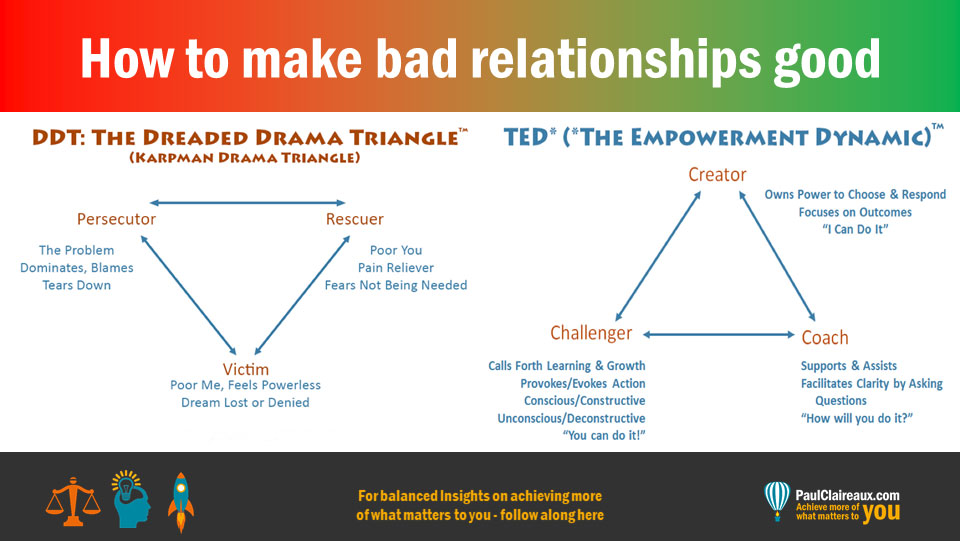

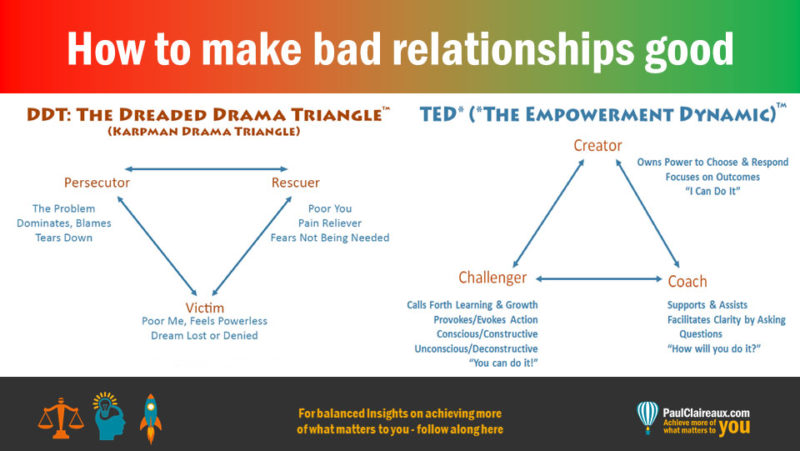

Playing the “Rescuer” role in Karpman’s drama triangle is false compassion based in sympathy, while playing the “Coach” role in the TED triangle is true compassion based in empathy.

Q: How is do-gooding behaving as the rescuer role in Karpman’s Drama Triangle? How might they be projecting their own inner victim onto the one they perceive as the victim, and then saving them as a means of saving their own inner child in an externalized fashion? Use my earlier example of social workers do-gooding in family law if you use any examples in your response.

A: Do-gooding aligns with the rescuer role in Karpman’s Drama Triangle by positioning the do-gooder as the savior who intervenes to “fix” a perceived victim’s plight, often casting an external force as the persecutor, thus perpetuating a cycle of dependency and drama rather than fostering true resolution. In this dynamic, the rescuer’s sympathetic impulse drives them to act—perhaps a social worker in family law hastily advocating for a child’s removal from a “neglectful” parent—without fully engaging the empathic process of understanding the victim’s reality or respecting their agency. This behavior feeds into the power-over-others game, as the rescuer gains a sense of purpose and moral authority by “saving” others, but their enmeshed approach lacks the boundaries needed to empower the victim to stand on their own. The triangle persists: the victim remains helpless, the persecutor (real or imagined) stays vilified, and the rescuer’s identity hinges on the ongoing crisis they unwittingly sustain.

The do-gooder’s projection of their inner victim onto the perceived victim reveals a subconscious motive: by rescuing the external “victim,” they seek to heal their own unaddressed inner child in an externalized manner, sidestepping personal accountability or self-reflection. For example, a social worker with a history of feeling powerless might see a child in a contentious divorce as a reflection of their younger, vulnerable self, projecting that inner wound onto the child and rushing to “save” them from a “toxic” parent. This act becomes a proxy for rescuing their own past helplessness—lifting the child out of perceived danger soothes their unresolved pain—but without boundaries, it blurs their identity with the victim’s, turning a professional duty into a personal crusade. Lacking empathy’s curiosity and differentiation, they miss the family’s true needs, their “help” serving their own emotional gaps more than the child’s well-being, thus risking harm under the banner of benevolence.

~Grok 3

I also follow the Foundation for Critical Thinking’s description of intellectual empathy, as seen in the definition above, and it adds breadth of thinking by adding angles and differing viewpoints. For instance, my reading a book from a Marxist would be considered intellectual empathy, because it’s an opposing view to my work as a classical liberal philosopher, but it doesn’t imply that I agree with or sanction other viewpoints, just that I understand them enough to formulate logically sound viewpoints and judgments, and make informed decisions based upon them. Intellectual empathy is a character trait that we can develop that assists us to gain a broader understanding of ourselves, other people, and the world we live in, which will lead to wise (compassionate) actions that have the potential to result in the highest good for all involved.

“He who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that. His reasons may be good, and no one may have been able to refute them. But if he is equally unable to refute the reasons on the opposite side, if he does not so much as know what they are, he has no ground for preferring either opinion… Nor is it enough that he should hear the opinions of adversaries from his own teachers, presented as they state them, and accompanied by what they offer as refutations. He must be able to hear them from persons who actually believe them…he must know them in their most plausible and persuasive form.” ~John Stuart Mill, On Liberty

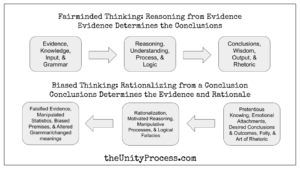

7. Reasoning from a Conclusion vs Reasoning from Evidence

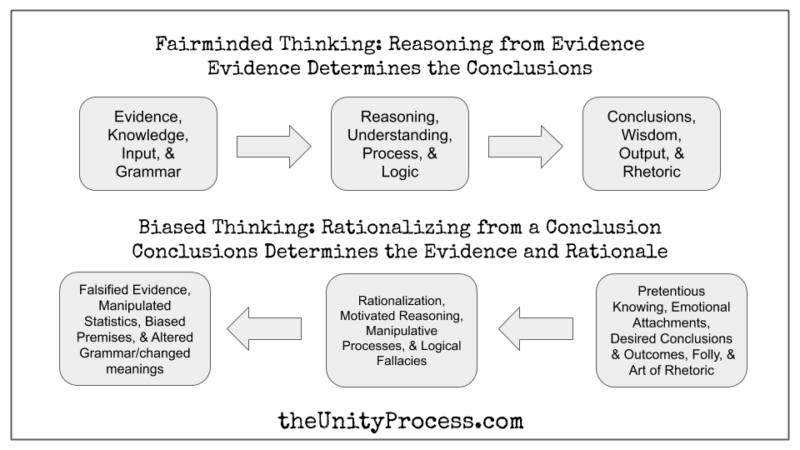

Q: What is the difference between reasoning from evidence and reasoning from a conclusion? How is reasoning from a conclusion similar to and/or aligned with sophistry? Why might reasoning from a conclusion be the result of being emotionally attached to a particular outcome and the cognitive dissonance that comes with it?

Q: What is the difference between reasoning from evidence and reasoning from a conclusion? How is reasoning from a conclusion similar to and/or aligned with sophistry? Why might reasoning from a conclusion be the result of being emotionally attached to a particular outcome and the cognitive dissonance that comes with it?

A: Reasoning from evidence involves building a conclusion based on observable facts, data, or logical premises, following a bottom-up process where the outcome emerges from what the evidence supports—think of a scientist testing a hypothesis and letting results shape the theory. In contrast, reasoning from a conclusion starts with a predetermined belief or outcome and works backward, selectively gathering or interpreting evidence to justify it, a top-down approach akin to a lawyer cherry-picking facts to defend a client they’ve already deemed innocent. The former seeks truth through open inquiry, like piecing together a puzzle without knowing the picture, while the latter defends a fixed position, molding the puzzle pieces to fit a chosen image, often ignoring what doesn’t align.

Reasoning from a conclusion mirrors sophistry—rhetoric aimed at winning arguments rather than uncovering truth—because both prioritize persuasion over accuracy, bending logic or evidence to serve a narrative. Sophists, as ancient Greek debaters, crafted plausible-sounding arguments to sway audiences, regardless of factual grounding, much like someone reasoning from a conclusion might twist data to “prove” a cherished belief, such as insisting a policy works despite contrary statistics. Both rely on rhetorical flair or selective framing—say, using emotional appeals or strawmen—to mask weak foundations, aligning with a power-over-others game where influence trumps reason. While sophistry is often deliberate, reasoning from a conclusion can be unconscious, yet both share a disregard for logos-driven inquiry, favoring victory or self-justification over objective understanding.

This backward reasoning often stems from emotional attachment to an outcome and the cognitive dissonance it triggers when faced with conflicting reality, driving a need to reconcile belief with evidence rather than revise the belief itself. If someone is invested in seeing a family member as flawless, they might dismiss signs of fault—reasoning from the conclusion of “they’re perfect”—because admitting otherwise causes discomfort, a clash between their attachment and the truth. Cognitive dissonance fuels this by pushing them to reduce tension, not through self-reflection, but by forcing evidence to fit, like a do-gooder social worker insisting a parent is a victim despite mixed facts, their sympathy clouding judgment. This emotional stake traps them in a cycle where the desired outcome—preserving their worldview—overrides rational process, making reasoning from a conclusion a shield against the vulnerability of being wrong.

~Grok 3

The next question is connected to section 17 on the drama triangle, because a victim mindset is one of the three aspects of the drama triangle of victim, persecutor, and rescuer. A victim mindset is one of the prime reasons why a person may feel compelled to discard all contradictory evidence and only reason from the starting assumption that they are a victim and that they need to be rescued from all of the external demons in their life, which are nothing more than internal demons that they fail to examine in a reflective manner.

Q: How might a victim mindset cause a person or people to reason from a conclusion rather than from evidence, as a means of supporting their certainty of their victim mindset?

A: A victim mindset can lead a person or group to reason from a conclusion rather than from evidence by anchoring their identity in the belief that they are perpetually wronged, prompting them to interpret reality through a lens that confirms this narrative over factual scrutiny. Someone steeped in victimhood might start with the conclusion “I’m always unfairly treated” and then selectively highlight instances—like a coworker’s offhand remark—while ignoring context or counterexamples, such as times they were supported. This top-down reasoning protects their certainty, as evidence is molded to fit the pre-set story of oppression rather than being allowed to challenge it, much like a puzzle forced into a distorted shape. The mindset thrives on externalizing blame, making it a psychological shortcut to avoid the discomfort of self-assessment or agency.

This tendency ties to an emotional need to preserve the victim identity, which offers both comfort and moral leverage, driving a cycle where reasoning from a conclusion becomes a defense mechanism against existential threats to that certainty. For a group, say a community claiming systemic disadvantage, the conclusion “we’re powerless” might lead them to dismiss data showing progress—like improved access to resources—as outliers, focusing only on setbacks to reinforce their collective victimhood. This mirrors sophistry’s persuasive bent: the goal isn’t truth but validation, using rhetorical weight (e.g., “no one understands our pain”) to rally sympathy or justify inaction. The victim mindset’s certainty provides a sense of righteousness or belonging, and evidence-based reasoning risks unraveling that, so they cling to a narrative that aligns with their emotional reality over objective analysis.

Cognitive dissonance further fuels this pattern, as confronting evidence that contradicts the victim conclusion—like personal successes or others’ fairness—creates tension between their self-perception and reality, pushing them to double down rather than adapt. An individual might feel dissonance if a promotion challenges their “I’m always overlooked” belief, so they reason backward, attributing it to luck or tokenism rather than merit, preserving their victimhood intact. This aligns with the power-over-others game indirectly: by staying victims, they can guilt-trip or manipulate others into rescuing them, as a do-gooder might rush in, while avoiding the logocentric truth game’s demand for self-reflection. Reasoning from a conclusion thus becomes a tool to sustain the victim mindset’s certainty, shielding them from the vulnerability of agency or the complexity of a world that isn’t wholly against them.

~Grok 3

Q: How might reasoning from a conclusion be associated with the “power over others game” and reasoning from evidence be associated with the “Logocentric truth game”?

A: Reasoning from a conclusion, often termed as reasoning backward or starting with the desired end to justify the means, aligns with the “power over others game” because it allows individuals or groups in power to manipulate narratives, evidence, or perceptions to fit their pre-decided outcomes. This method can be used to maintain control, justify authoritarian decisions, or sway public opinion by selectively presenting or interpreting facts to support the conclusion that benefits those in power, thus reinforcing their dominance or agenda without regard for actual truth or fairness.

Conversely, reasoning from evidence is central to the “Logocentric truth game,” where the pursuit is for truth and understanding based on objective facts and logical analysis. This approach involves gathering evidence first and then drawing conclusions based on that evidence, fostering an environment where arguments are evaluated on their merit, not on who presents them or what power they hold. This method encourages a discourse where truth is sought through reason, transparency, and critical examination, aiming for conclusions that are as close to objective reality as possible, promoting justice, fairness, and intellectual integrity over power dynamics.

~Grok2

Q: How might being outcome oriented be related to the power over others game and being process oriented be related to the Logocentric truth game?

A: Being outcome-oriented aligns with the “power over others” game because it prioritizes achieving specific ends—such as status, control, or victory—often at the expense of ethics, relationships, or truth, making it a natural fit for manipulative strategies like projection or enforced sacrifice. An outcome-oriented individual or institution might focus solely on winning, whether it’s a promotion, a political campaign, or a personal dispute, and employ tactics like scapegoating or performative altruism to secure dominance. For example, a manager obsessed with hitting sales targets might project blame onto a struggling team member and demand their “sacrificial” overtime, caring little for fairness or morale as long as the numbers are met. This fixation on results over how they’re achieved fuels a dynamic where power is gained by bending others to one’s will, sidelining introspection or mutual benefit in favor of tangible leverage.

In contrast, being process-oriented relates to the “logocentric truth game” because it emphasizes the integrity of the journey—how one thinks, acts, and grows—over predetermined endpoints, aligning with a pursuit of rational clarity and authenticity rooted in logos. A process-oriented person values self-reflection and the consistent application of reason, focusing on understanding why something happens or how it can be improved, rather than just what can be gained. For instance, a scientist exploring a hypothesis might prioritize refining their method and learning from failures over forcing a desired conclusion, embodying a commitment to truth over ego or external reward. This approach resists the power-over-others game by rejecting shortcuts like manipulation, instead building knowledge and self-awareness through deliberate, honest steps that honor the present moment and its lessons.

The tension between these orientations highlights their deeper implications: outcome-orientation drives the power game by treating others as means to an end, while process-orientation supports the truth game by treating the self and the world as ends worthy of understanding. A politician fixated on election victory might smear opponents with projected flaws to sway voters, their eyes locked on the outcome of power, heedless of the process’s dishonesty. Meanwhile, a philosopher or educator focused on process might patiently unpack a complex idea through dialogue, valuing the clarity gained over any immediate win, embodying a logocentric fidelity to reason. The former thrives on control and external validation, often leaving collateral damage; the latter cultivates autonomy and insight, fostering a legacy of integrity that endures beyond fleeting triumphs. Thus, outcome-orientation bends toward dominance, while process-orientation leans into discovery, each reflecting its respective game’s core ethos.

8. Subjective Morality vs Objective Morality

Subjective morality is when one’s subjective preferences, traditions, and beliefs take precedence over objective laws and principles, themselves being deified as equal to or higher than objective truth itself.

Objective morality is an objective sense of right and wrong that transcends human tradition and societal norms; can be extrapolated from the use of reason alone. It is far more beneficial when it is discovered and cultivated from within rather than imposed from without.

Logos is the objectively moral blueprint underlying all of reality, consisting of reason, universal intellectual standards such as clarity, breadth, depth, and fairmindedness, intellectual character traits such as humility, empathy, courage, and autonomy, natural/universal law and natural rights, care, and love. All of these things can be found within each individual, however, once found, they must also be willfully cultivated and integrated into one’s personality as a grounded foundation and means of governing oneself.

The ability to process together with another using reason is able to forgive sins/debts, which is why Logos is considered to be intimately connected to the person of Jesus in Christianity and other mystical circles. Processing one’s emotional upsets, along with other sins, debts, and karmic consequences, especially with a coach type figure from the TED* triangle, can help one align one’s character more and more with objective moral principles through gaining understanding, and this leads one to wisdom/God/heaven.

Come now, and let us reason together, saith the Lord: though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be as white as snow; though they be red like crimson, they shall be as wool. ~Isaiah 1:18 KJV

Jesus answered, “I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father (to wisdom/God/heaven) except through me (understanding). ~John 14:6

According to Ayn Rand and a few other mystics and philosophers, morality is objective and grounded in reason, also known as natural law or the law of reason.

A rational process is a moral process. You may make an error at any step of it, with nothing to protect you but your own severity, or you may try to cheat, to fake the evidence and evade the effort of the quest – but if devotion to the truth is the hallmark of morality, then there is no greater, nobler, more heroic form of devotion than the act of a man who assumes the responsibility of thinking. ~Ayn Rand

Q: What is natural law, and how is it objectively moral rather than subjectively moral? How would John Locke and St Thomas Aquinas define natural law, and do they believe it to be objectively based upon reason or upon subjective standards?

A: Natural Law is a philosophical and legal theory that posits there are inherent moral principles embedded within the fabric of the universe and human nature, which can be discerned through reason. These laws are considered ‘natural’ because they are believed to be part of the order of things, independent of human-made laws or cultural variations. Natural law asserts that certain actions are morally right or wrong based on their alignment with human nature and the natural order, thus providing an objective standard for morality. This objectivity stems from the idea that there are certain truths about human existence and the world that are discoverable by rational inquiry, not subject to individual whims or cultural relativism.

John Locke defines natural law as a set of moral principles derived from reason that govern human conduct in a state of nature. In his “Two Treatises of Government,” Locke argues that natural law is the law of reason, which teaches that all humans, being equal and independent, should not harm each other in their life, health, liberty, or possessions. Locke views natural law as objectively moral because it’s based on the rational capacity of humans to understand their rights and obligations in the natural state. For Locke, the objectivity lies in the rational discovery of these laws, which are universally applicable, thus not dependent on subjective standards or cultural contexts but on human nature itself.

St. Thomas Aquinas, in his “Summa Theologica,” describes natural law as the rational creature’s participation in the eternal law of God, which is accessible through reason. He divides natural law into primary and secondary precepts, with the primary being self-evident principles like “do good and avoid evil.” Aquinas sees natural law as objectively moral because it reflects the immutable divine law, yet it is discoverable by human reason. The objectivity here comes from the belief that these moral truths are part of God’s eternal law, which humans can understand through their rational faculties. Aquinas, like Locke, believes in an objective moral order based on reason, though his foundation is theological, suggesting that while human reason can grasp these truths, they are ultimately part of a divine scheme. Both philosophers advocate for an objective moral framework, but their bases for this objectivity differ, with Locke focusing on human nature and Aquinas on divine law interpreted through human reason.

~Grok2 AI

Q: Why did Ayn Rand believe that morality and reason are interconnected? What moral rules was she able to discern through the use of reason?

A: Ayn Rand believed that morality and reason are interconnected because she viewed human life and flourishing as fundamentally dependent on the rational use of one’s mind. In her philosophy of Objectivism, reason is the human faculty for identifying and integrating the facts of reality, making it the primary tool for survival and well-being. Morality, therefore, must be based on reason because ethical principles should guide human action in accordance with objective reality. According to Rand, any moral system that contradicts reason undermines human life, as it leads individuals away from the facts of their existence and their needs. She argued that morality should not be derived from arbitrary sources like divine commandments, societal norms, or emotional whims but from the objective necessity of human life, where reason becomes the moral standard.

Through her application of reason, Rand discerned several moral rules that she believed were essential for human life. These include the virtue of egoism, where acting in one’s rational self-interest leads to personal happiness and, by extension, benefits society through productive and creative endeavors. She emphasized individual rights, particularly the right to life, liberty, property, and the pursuit of happiness, as these rights allow for the exercise of reason and the achievement of one’s values. Other moral rules she deduced include honesty, which is necessary for a rational interaction with reality; independence, encouraging individuals to think for themselves; integrity, to live consistently with one’s rational principles; productivity, as a moral obligation to use one’s mind to improve one’s life; and justice, ensuring that each person gets what they objectively deserve based on merit. These principles, according to Rand, form the basis of a rational moral code that promotes human flourishing.

~Grok2 AI

I’d like to address the elephant in the room where on the one hand, reason can be compared to the fire of Prometheus that was stolen from the gods and granted to mankind as a means of “being like God” in the creative process, and how it can help us to determine what is and is not moral, and on the other hand, Ayn Rand’s atheism. While she was a staunch atheist, I do not believe that we must throw out the baby with the bathwater in regards to the possibility of Divine presence and/or influence in our lives. She lived in a time when people were forfeiting their moral responsibility to reason over to their church and/or God, and in many ways, this idea persists today as well. As long as we are seeing reason as Logos, the Divine principles of God, the two concepts can and should co-exist, however, I will add that Ayn Rand, at least on paper in my book, would be considered more moral than many religious adherents, priests, pastors, rabbis, etc., due to her adherence to reason based morality. Any moral precept, from a religious text or not, should be judged by reason to determine whether or not it is universally applicable and objectively moral, and not because “God said so in the Bible”, which is the logical fallacy (deception) of “circular reasoning”; lies and fallacies should never be used to support the truth.

Dennis Prager, a practicing Orthodox Jew and notable political conservative, had this to say about reason and Divinity, and I concur with his conclusion: