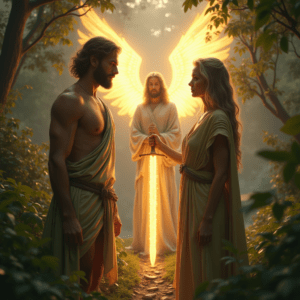

The Genesis account of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden provides a foundational narrative for understanding the loss of innocence, particularly in the moment when they sew fig leaves to cover themselves after eating from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil (Genesis 3:7). Before this act, their nakedness carried no shame (Genesis 2:25), suggesting that their innocence functioned as a natural garment, a state of unselfconscious purity resonant with John Locke’s vision of a “perfect state of nature” where harmony and freedom prevail without societal distortion. However, once they partake of the forbidden fruit, this innocence is replaced by shame and guilt, emotions that become their new “clothing”—an illusory covering akin to the Emperor’s nonexistent robes in Hans Christian Andersen’s tale, invisible yet oppressively felt. This shift marks a profound transition from a proud, unblemished existence to one shadowed by moral awareness and vulnerability, setting the stage for humanity’s complex relationship with its own flaws.

The Genesis account of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden provides a foundational narrative for understanding the loss of innocence, particularly in the moment when they sew fig leaves to cover themselves after eating from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil (Genesis 3:7). Before this act, their nakedness carried no shame (Genesis 2:25), suggesting that their innocence functioned as a natural garment, a state of unselfconscious purity resonant with John Locke’s vision of a “perfect state of nature” where harmony and freedom prevail without societal distortion. However, once they partake of the forbidden fruit, this innocence is replaced by shame and guilt, emotions that become their new “clothing”—an illusory covering akin to the Emperor’s nonexistent robes in Hans Christian Andersen’s tale, invisible yet oppressively felt. This shift marks a profound transition from a proud, unblemished existence to one shadowed by moral awareness and vulnerability, setting the stage for humanity’s complex relationship with its own flaws.

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that explores the fundamental nature of reality, existence, and the relationships between mind, matter, and the universe, often addressing questions about being, causality, and the nature of the divine.

Narcissism is a personality trait marked by an inflated sense of self-worth, a constant need for validation, and a lack of empathy, often rooted in deep-seated toxic shame that creates an inner sense of inferiority. To mask this vulnerability, narcissists employ exploitative techniques, such as manipulation and projection, to shift their shame onto others while maintaining a façade of superiority.

In the Garden of Eden story from Genesis, Adam and Eve live in a state of innocent harmony until the serpent tempts them to eat from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, awakening them to their nakedness and moral awareness (Genesis 3:1-7). After disobeying God, they feel shame and guilt, hastily covering themselves with fig leaves and hiding, marking the loss of their untainted state (Genesis 3:8-10). This narrative frames humanity’s fall from grace, where the acquisition of knowledge introduces shame and guilt, forever altering their relationship with themselves and the divine.

Shame is an emotional state where an individual internalizes a sense of fundamental flaw or unworthiness, often expressed as “I am wrong” in the core of their being. It differs from guilt by targeting the self rather than a specific action, encompassing a pervasive feeling of disgrace or inadequacy.

Guilt, conversely, arises from recognizing a specific misdeed, encapsulated as “I did wrong,” focusing on the act rather than the person’s identity. It motivates remorse or a desire to make amends, remaining distinct from shame’s broader self-condemnation.

In Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” a vain ruler is deceived by swindlers who claim to weave invisible fabric, which only the wise can see, prompting him to parade naked while his subjects pretend to admire his nonexistent attire. The illusion persists until an innocent child, free from social pretense, declares the Emperor naked, shattering the collective delusion with simple truth. The tale satirizes arrogance and conformity, highlighting how fear of exposure can sustain a lie until innocence intervenes.

Psychologically, this transformation aligns with modern distinctions between guilt and shame, as articulated by June Price Tangney in Self-Conscious Emotions (1995), where guilt reflects remorse for a specific act—like eating the fruit—while shame encompasses a broader condemnation of the self, evident in Adam and Eve’s sudden awareness of their nakedness. Their immediate impulse to hide from God (Genesis 3:8) and cover themselves with leaves suggests a dual burden: guilt driving their retreat and shame amplifying their exposure, a dynamic Jean-Paul Sartre explores in Being and Nothingness (1943) through “the look,” where the gaze of another (or self) objectifies and intensifies self-consciousness. Theologically, St. Augustine in City of God (Book XIV) interprets this as the consequence of disobedience, a fall from original righteousness that strips away innocence and cloaks humanity in a persistent sense of unworthiness. Together, these perspectives frame the Edenic narrative as a psychological and spiritual archetype for the human experience of losing purity to the weight of moral failure.

Narcissists, often developmentally arrested by early childhood wounds as Heinz Kohut describes in The Analysis of the Self (1971), may exploit this vulnerability by appropriating the innocence of others through mechanisms like scapegoating, false accusations, and shadow projection. By casting their own shame and guilt onto their victims—much like the Emperor donning imaginary clothes to mask his nakedness—they maintain an illusion of moral superiority while forcing their prey to wear the “nakedness” of their shed flaws, a process akin to Melanie Klein’s projective identification from Notes on Some Schizoid Mechanisms (1946). This perverse inversion of the Edenic story suggests that innocence isn’t merely lost but can be stolen, allowing the narcissist to parade in stolen purity while their targets grapple with an imposed sense of guilt and exposure. Such a dynamic reveals a deeper moral theft, where the narcissist’s shallow self-preservation comes at the cost of another’s authenticity, peace, good name, and innocence.

Consider the possibility that the serpent in Genesis orchestrates this very theft, deceiving Adam and Eve out of their innocence due to their naiveté and wearing it as a deceptive cloak while leaving them to bear its shame. Described as “more crafty than any of the wild animals” in Genesis, the serpent—often identified with Satan in Christian tradition—might have appeared innocent or trustworthy, exploiting their lack of moral discernment to strip them of their natural garment (innocence) and replace it with shame and guilt. This act of shedding shame, much like a snake sheds its skin, positions the serpent as the original narcissist, donning their purity to perpetuate its ruse while Adam and Eve scramble to cover themselves with fig leaves, now clad in the serpent’s discarded burden. This interpretation casts the Fall as not just a loss but a deliberate usurpation, initiating a cycle where innocence is perpetually targeted by cunning deception, and ultimately fed upon (loosh farming).

This cycle finds a chilling echo in Cain’s murder of Abel, where the pattern of scapegoating and shame displacement continues unabated through human history. Driven by envy and unwilling to confront his own inadequacy and shame, Cain kills his innocent brother, much as Adam shifts blame to Eve (“The woman you put here with me,” Genesis 3:12), effectively cloaking himself in Abel’s virtue while Abel’s blood marks the earth with undeserved shame—a perpetuation of the serpent’s legacy. Theologically, Augustine in City of God sees this as the unfolding of original sin’s consequences, a ripple effect where the innocent suffer for the guilty, while psychologically, it mirrors the narcissist’s habit of externalizing flaws onto others to preserve a fragile self-image. Cain, marked yet unrepentant, strides forth like the Emperor, his “new clothes” of innocence woven from his brother’s stolen righteousness, illustrating how the Edenic deception embeds itself into human behavior.

The serpent’s shedding of skin emerges as a potent metaphor for Satan’s narcissistic ability to discard shame and guilt, replacing them with the innocence stolen from others in a cunning act of reinvention. In Genesis 3:6, it promises enlightenment but delivers disgrace, shedding its own moral burden—rooted in its rebellion against God (Isaiah 14:12-15)—and wrapping itself in Adam and Eve’s purity, a process Jung’s shadow projection in Psychology and Religion (1938) illuminates as the externalization of inner darkness. This allows the serpent to slither away untainted, leaving humanity to inherit its shed shame, a dynamic that underscores its ability to thrive by inverting accountability and masquerading as virtuous. Such a metaphor highlights a fundamental trait of narcissism: the capacity to renew oneself at others’ expense, wearing the light of their prey as a disguise while their prey stumbles under the weight of imposed darkness (projected shame and guilt).

In the Gnostic text Hypostasis of the Archons, this narcissism reaches a cosmic scale with Samael, who arrogantly declares himself the one true God, a boast reflecting a god complex born from stolen innocence and projected shame. Blind to the higher divine realm, Samael rules a material world he deems supreme, his self-deification a delusion Jung might describe as ego inflation, where the narcissist compensates for inner flaws by claiming grandiose omnipotence. This elevates the serpent’s Edenic trickery into a metaphysical usurpation, where innocence is not just taken but used to construct a fraudulent throne, leaving humanity to bear the shame and guilt of his flawed existence. Samael’s story thus amplifies the theme of narcissism as a theft of purity that fuels an illusory sense of divinity, a pattern rooted in the Garden’s deception.

The act of stealing innocence often breeds this god complex in narcissists, as their ability to skirt the debt/sin of karmic cause and effect through projection imitates a divine immunity to consequences. By shedding their shame onto others, as Kohut’s narcissistic framework suggests, they maintain an untouchable facade, strutting in the stolen purity of their victims while those victims wrestle with an unjust burden of shame and guilt—a dynamic Samael epitomizes in his arrogant reign. This evasion of accountability and liability, where the innocent wear the narcissist’s shame, mirrors the serpent’s triumph in Eden and Cain’s unpunished mark, reinforcing a delusion of omnipotence that collapses only when confronted by truth that is accompanied with tangible consequences. Philosophically, this aligns with Sartre’s “bad faith” in Being and Nothingness, a refusal to face one’s own nakedness that sustains the narcissist’s hollow grandeur at others’ expense.

Ironically, in Andersen’s The Emperor’s New Clothes, it is an innocent child who dismantles this illusion, declaring the Emperor naked with a clarity untainted by social complicity or projected shame. This childlike purity, resonant with the biblical call to “become like little children” (Matthew 18:3), holds a unique power to pierce the narcissist’s borrowed garb, exposing the truth that the crowd, blinded by their own participation, cannot see. The boy’s unselfconscious honesty unravels the Emperor’s stolen innocence, suggesting that the very quality narcissists exploit—innocence—can also be their undoing when it refuses to bend to their deception. This moment hints at a fragility in the god complex: the narcissist’s reign persists only until innocence, uncorrupted, names the nakedness beneath the lie.

The crucifixion of Jesus presents a climactic instance of this pattern, where the mob projects its collective shame and guilt onto the innocent, demanding Barabbas’ release over Christ’s life (Matthew 27:15-26). In this act, they externalize their darkness onto Jesus, the sinless scapegoat, who absorbs it willingly—a ritual René Girard in The Scapegoat (1986) identifies as society’s redirection of violence to purge its own sins, a theological cornerstone where “God made him who had no sin to be sin for us” (2 Corinthians 5:21). The crowd’s participation mirrors the narcissist’s shadow projection, choosing a murderer’s freedom to cloak their shame in Jesus’ suffering, yet His acceptance transforms this burden into redemption rather than mere exposure. This event starkly contrasts the Emperor’s fleeting delusion, offering a resolution where innocence doesn’t just reveal but redeems the shame and guilt it bears.

Unlike the Emperor’s temporary triumph, Jesus’ crucifixion breaks the cycle of narcissistic projection by embracing the shame thrust upon Him, exposing the mob’s nakedness while extending grace. Where the serpent, Cain, and Samael perpetuate a legacy of stolen innocence and shed shame and guilt, Jesus’ sacrifice—foreshadowed by God’s provision of skins in Genesis 3:21—offers a counterpoint, a willing assumption of humanity’s burden that shatters the narcissist’s god complex with humility and truth. This redemptive act reframes the Edenic fall, suggesting that innocence, though vulnerable to theft, can reclaim its power not through naiveté but through conscious sacrifice, turning the scapegoat’s shame into a pathway to restoration. The contrast illuminates a deeper truth: the narcissist’s illusory reign falters when innocence, whether through a child’s observation or a savior’s innocence nailed to a cross, asserts its enduring strength.

These interwoven narratives—from Eden’s serpent to Cain’s violence, Samael’s arrogance, the Emperor’s ruse, and Christ’s crucifixion—reveal a persistent human struggle with innocence, shame, and the narcissistic impulse to displace shame and guilt onto others. The narcissist, whether a biblical deceiver or a literary monarch, thrives by stealing purity and cloaking themselves in it, leaving the innocent to wear their shed flaws, a cycle that promises impunity but crumbles under truth’s conscious gaze. Yet, across these tales, innocence emerges as both victim and victor—exploited yet capable of exposing and redeeming, whether through a boy’s unfiltered voice or a messiah’s silent endurance. This tension reflects humanity’s ongoing dance with its own nature, caught between the serpent’s shed skin and the cross’s offered garment, yearning for a return to the purity once lost in the garden.

Did you enjoy the article? Show your appreciation and buy me a coffee:

Bitcoin: bc1qmevs7evjxx2f3asapytt8jv8vt0et5q0tkct32

Doge: DBLkU7R4fd9VsMKimi7X8EtMnDJPUdnWrZ

XRP: r4pwVyTu2UwpcM7ZXavt98AgFXRLre52aj

MATIC: 0xEf62e7C4Eaf72504de70f28CDf43D1b382c8263F

THE UNITY PROCESS: I’ve created an integrative methodology called the Unity Process, which combines the philosophy of Natural Law, the Trivium Method, Socratic Questioning, Jungian shadow work, and Meridian Tapping—into an easy to use system that allows people to process their emotional upsets, work through trauma, correct poor thinking, discover meaning, set healthy boundaries, refine their viewpoints, and to achieve a positive focus. You can give it a try by contacting me for a private session.

One Response to “The Metaphysics of Narcissism: Stealing Innocence & the Emperor’s New Clothes”

Read below or add a comment...

Trackbacks

[…] must reject the illusion of moral authority created by coercive power (as discussed in a previous article, innocence may also be able to break the spell). Parents, children, and even agents of the state […]